DENVER — The United States asked the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals on Wednesday to examine American Samoa’s political relationship with the United States and overturn a lower court’s ruling that determined those born in the Pacific Islands are in fact American citizens.

American Samoa has been a U.S. territory since 1900 and has the highest rate of military service in the U.S. Those born in the cluster of Polynesian islands 2,500 miles southwest of Hawaii, however, are American nationals — not citizens. They cannot vote or run for office in the incorporated U.S. or hold certain government jobs.

The government of American Samoa argued his arrangement preserves the islanders’ traditional way of life, or fa’a Samoa, including communal property ownership which would be impossible to protect under the U.S. Constitution.

American Samoa was unique from other U.S. territories Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands where persons become citizens at birth. That is until George W. Bush-appointed U.S. District Judge Clark Waddoups in the District of Utah made history on Dec. 12, 2019, by ruling American Samoans should no longer be denied birthright citizenship.

“Right now the American Samoa people have a degree of self-determination and would like a say in a way that protects their culture,” attorney Michael Williams of Washington firm Kirkland & Ellis told the 10th Circuit panel. “At the same time, individuals from American Samoans not only have a path to citizenship, but a glide path to citizenship, they have an expedited path to citizenship if they leave American Samoa and reside in a state of the union.”

Williams referred to the Philippines and the Federated States of Micronesia, as well as the Marianas which negotiated their own terms with the U.S.

“It is for Congress to determine whether and under what circumstances individuals born in American Samoa and other territories become citizens,” argued Department of Justice attorney Brad Hinshelwood.

“It would really be a pretty dramatic shift between our understanding of the relationship between the United States and the territories to hold that after all this time everyone born in the Philippines for 50 years was in fact a U.S. citizen and no one knew it,” he added.

Following the Spanish American War, the Philippines were also a territory of the U.S. from 1898 until 1946.

Nevertheless, attorney Matthew McGill, of the Washington D.C. firm Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher called his client, John Fitisemanu a modern-day Dred Scott, “a citizen of nowhere.”

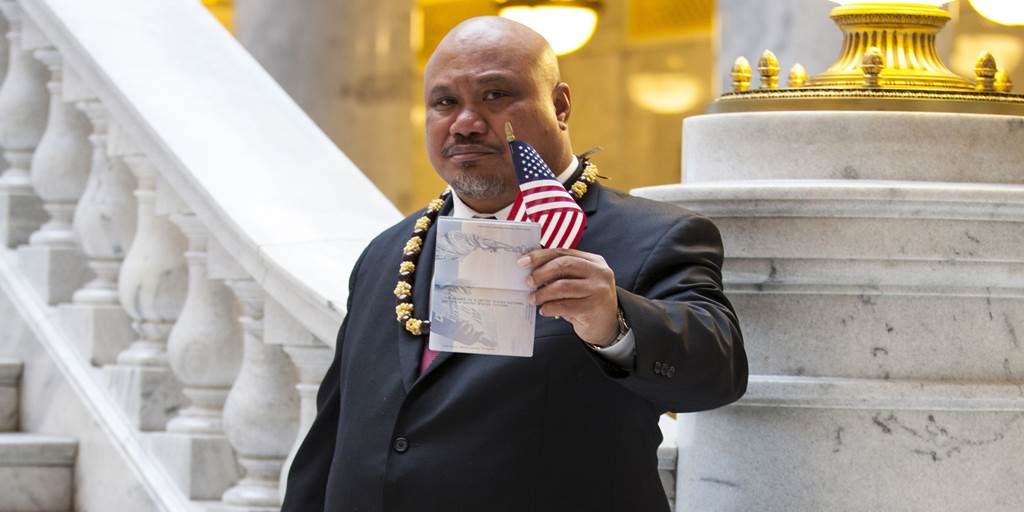

Born in American Samoa, on U.S. soil in 1965, Fitisemanu built his life in Utah and works in the health care industry. He pays federal, state and local taxes and sent his four children to Utah public schools. He holds a U.S. passport that is imprinted with a code that labels him as a “non-citizen national.”

“The United States is asking you to embrace the very most indefensible aspects of the insular cases that birthright citizenship could not possibly apply to people born on ‘an unknown island peopled with an uncivilized race,’” McGill said. “If the citizenship clause does not apply to the territories then a person naturalized in the territories would be not guaranteed citizenship in the incorporated states either.”

U.S. Circuit Judge Carlos Lucero, appointed by Bill Clinton, appeared most concerned about whether the people of American Samoa had a voice and were being heard.

“Do the citizens of territories under which occupancy has occurred by the United States have no say so as to their citizenship?” Lucero asked. “Here you’re saying the citizens at the time of succession had no choice, and I have a pretty harsh position to take if they don’t want citizenship.”

McGill said citizenship arose once the American flag went up.

“The only question is whether territories are part of the United States for the purpose of the citizenship clause,” McGill said. “The central purpose of the citizenship clause was to remove the question of birthright citizenship from the realm of politics. We had just fought a war of unimaginable bloodshed, over who would be a citizen in our polity and whether dissenters could leave, so the reconstruction congress was clear.”

Chief U.S. Circuit Judge Timothy Tymkovich, appointed by George W. Bush and U.S. Circuit Judge Robert Bacharach, a Barack Obama appointee, rounded out the panel. They did not indicate when or how they would decide the case.

Sixty-two viewers tuned into the hearing held remotely due to the COVID-19 pandemic and broadcast live by the 10th Circuit on YouTube.