CHARLOTTE AMALIE — Federal prosecutors are fighting to limit how and when Charlotte Amalie High School track coach and hall monitor Alfredo Bruce Smith can review evidence against him — including sexually explicit videos and documents involving underage students, as first reported in the Virgin Islands Daily News.

U.S. District Court Magistrate Judge Ruth Miller held an arraignment hearing Wednesday morning, where Federal Public Defender Matthew Campbell entered a not guilty plea to all charges on Smith’s behalf.

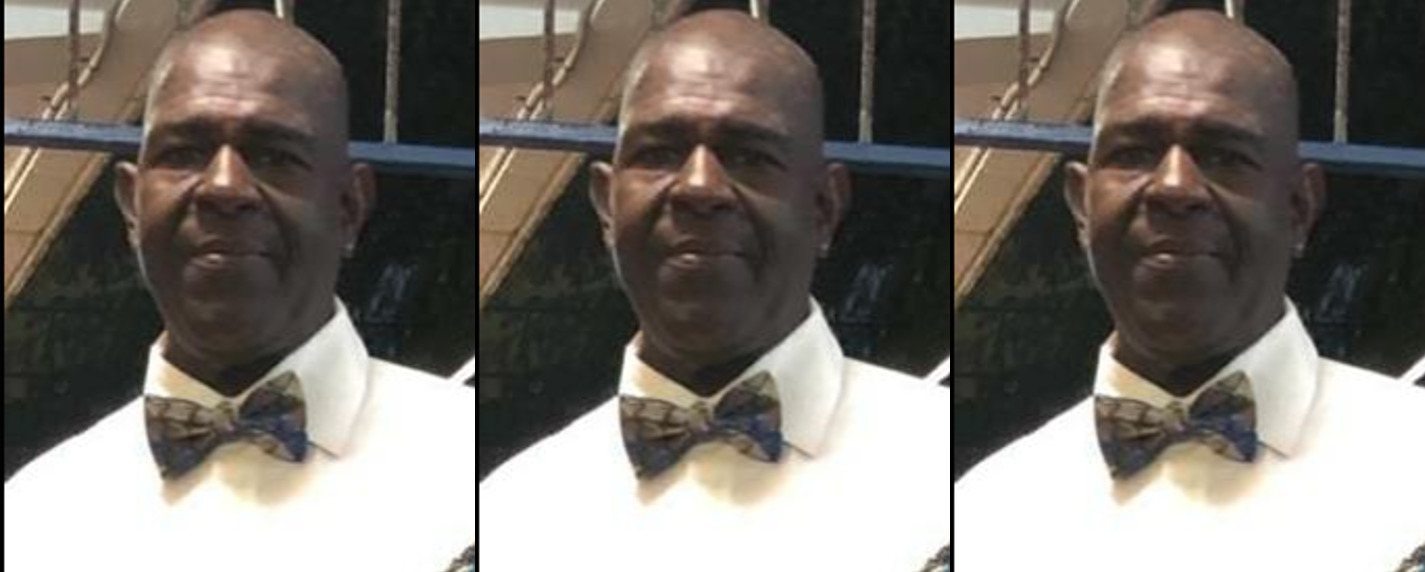

Smith, 50, has been employed at Charlotte Amalie High School for 15 years. He was charged September 1 with production of child pornography, and on September 30, prosecutors formally charged Smith with 13 criminal counts: three counts of aggravated second-degree rape, seven counts of coercion and enticement, two counts of sexual exploitation of a child, and transportation with intent to engage in criminal sexual activity. The charges involve seven minor victims who were abused between January 2014 and October 2020.

Federal prosecutors say they have evidence indicating that Smith sexually abused dozens of underage boys for at least 13 years, and filmed himself raping students in the school, according to court documents.

Miller said trial is scheduled to begin on December 13 and set a deadline for discovery of November 3, which Assistant U.S. Attorney Natasha Baker said would be “virtually impossible in this case.”

The government is seeking to designate the case as complex, so prosecutors can be relieved of having to meet speedy trial deadlines, and have more time to review and prepare evidence.

Prosecutors are also asking for a protective order that would prohibit the defense from having full, unfettered access to discovery materials.

The law already restricts the government from distributing videos of child sexual abuse, and Campbell and Smith must review such materials in the U.S. Attorney’s office, on government computers.

But Baker is asking the court to go a step further and issue a protective order for all materials that contain a victim’s “name or any other information,” and “the defense feels that’s too broad,” Miller said.

Baker argued that certain pieces of information could be used to identify victims, even with their name, address, and other identification redacted, particularly “in this small community where everyone kind of knows each other.”

“We’re talking about discovery in a criminal case and the Constitutional rights of the defendant,” Miller said. “We’re not talking about having it out in the public and getting discussed on Facebook. We’re talking about the defendant having the opportunity to view the evidence against him so he can properly prepare for trial.”

“The defendant can review all of that, no problem, we just don’t want him to have copies of them in the jail setting,” Baker said.

Smith has been jailed at the Metropolitan Detention Center in Puerto Rico since his arrest, and in that time “we haven’t seen a page of discovery,” Campbell said.

Baker agreed to let Campbell review discovery so he can gauge the volume of evidence involved, but he expressed concern with prosecutors’ desire to tightly control where and when Smith can review discovery.

“I’m struggling with the government’s argument regarding this being a small community, or people might be able to understand who people are. That’s not statutory language, that’s not from my review, reflected in the case law. The reason why I’m having trouble with this language is because it essentially would sweep in every bit of discovery, everything,” Campbell said.

Based on the government’s representation of “the size of the discovery and gigabytes to date, this is not a question of reviewing discovery over a day, or a couple of days or weeks. Discovery review in this case could take months,” Campbell said. “And frankly, if I am required to sit next to Mr. Smith and review every page of millions of pages, or hundreds of hours of video, that isn’t workable. I would need to move to Puerto Rico and effectively sit there for four months.”

Miller asked whether a room can be set up at the jail where Smith can access discovery securely, as has been done in other cases.

Campbell said that seemed like the best option, but there is still dispute over which pieces of evidence constitute child pornography, which must be reviewed on the prosecutors’ computers, in their office.

The parties are “far apart” in that discussion, Campbell said.

Baker said the materials came from Smith’s devices and “he knows what’s there. We’re not trying to hide anything from him,” only ensure the victims are not publicly identified.

Miller said the case has “a trial date not too far down the road,” and could theoretically move quickly.

“Voluminous discovery, or what appears to be voluminous discovery does not a complex case make, so you need to be prepared to do whatever you need to do to get the discovery produced, notwithstanding that there’s a lot of it,” Miller said.

She also expressed concern with the government’s broad definition of what should be considered confidential, including all materials “concerning a child.”

“Given the charges in this case, ‘concerning a child’ covers pretty much everything, I would suggest. Or potentially could and should cover just about everything,” Miller said. “So, I appreciate your saying it’s a limited amount, but that language is extraordinarily broad.”

On a practical level, the court is facing a “major challenge” in ensuring Smith has access to the sensitive materials “when he’s housed on a different island in a detention situation. That’s what we’re dealing with. So, we need to get focused in on how to make this happen and preserve everybody’s rights — the victims, the defendant, whoever,” Miller added.

She scheduled a pretrial conference for November 3.

By SUZANNE CARLSON/The Virgin Islands Daily News