MIAMI — A little more than three years ago, as sports bar TVs were split between coronavirus infection tallies and the XFL, a more subtle but no less extreme scourge was taking shape across the tropical oceans.

La Niña, defined by colder than normal sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the Central Pacific, developed in the summer of 2020. Since then, as everything else has changed other than the 99-cent price of AriZona iced tea, global weather patterns have consistently been in the thrall of the third-longest Niña on record. Like the world’s worst gender reveal, the 2020-23 La Niña’s résumé included staggering drought in the Plains and Florida’s “winters” lasting around 4 days.

In the Tropics, La Niña also fomented the busiest three-year period for the continental U.S. since the 1930s, with a total of 25 (!) tropical storm, eleven hurricane, and four major hurricane strikes. In each of the 2020, 2021, and 2022 seasons, the Gulf Coast suffered a catastrophic Category 4 hurricane landfall, culminating with Ian’s $113 billion lapidation of Southwest Florida.

And yet, with the demise of La Niña this March, an unfamiliar feeling hides in the corner of the Pandora’s Box that is hurricane season: hope.

What are the odds of a normal hurricane season?

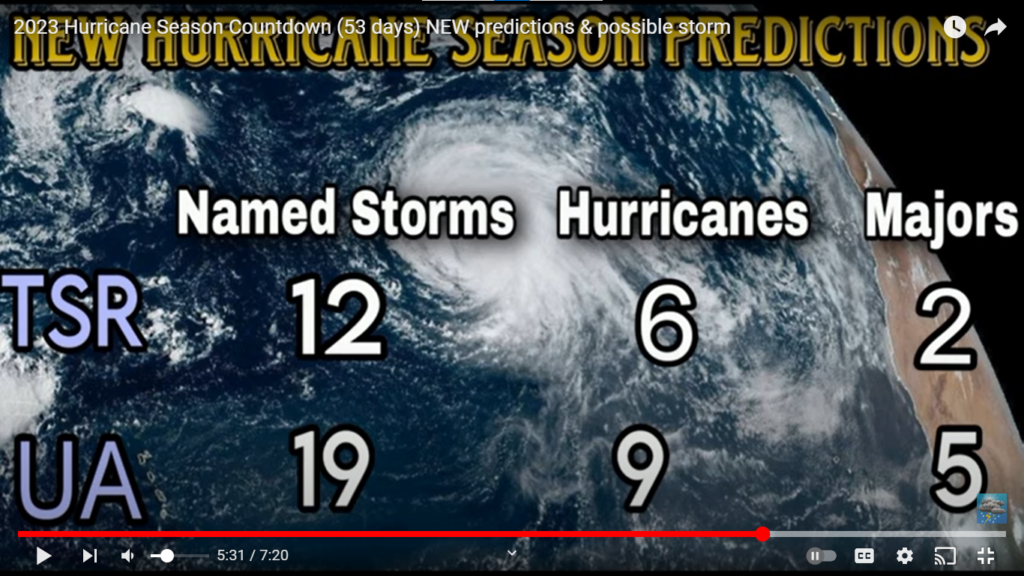

WeatherTiger’s initial forecast for the 2023 Atlantic season holds out around a 70% chance of normal or below normal tropical activity in the year ahead, projecting a most likely outcome of around 90% to 95% of 1950-2022 averages.

This corresponds to odds of a below normal (<75 Accumulated Cyclone Energy units) at 35%, normal (75-125 ACE) at about 35%, or above normal (>125 ACE) season at about 30%. The ’23 season has a 50-50 shot of landing somewhere between 65-135 ACE units, 13-18 tropical storms, 5-8 hurricanes, and 2-3 major hurricanes.

The reason for this cautious optimism is that Atlantic hurricane activity has a strong relationship with the multi-year cycle of abnormally warm (El Niño) or cool (La Niña) waters in the Equatorial Pacific known as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO). As summer and fall El Niños are often linked to hurricane-weakening wind shear in the Atlantic, La Niña hurricane seasons average about 75% more tropical activity than El Niño years.

The disparity is even more stark in terms of what really matters, stronger storms impacting land. In Florida, La Niña seasons since 1900 have notched an average of 0.8 hurricane landfalls per year, compared with around 0.4 hurricane landfalls per year during El Niños. Roughly doubled hurricane risks in La Niña versus El Niño seasons, with neutral years somewhere in the middle, holds true for U.S. landfalls as well.

Unfortunately, spring projections face a “predictability barrier” of diminished forecast skill due to the susceptibility of the Pacific to sudden shifts. In 2023, the ENSO outlook is a riddle wrapped in an enigma, like the bizarre names found on the backs of the original XFL uniforms, including those of the Orlando Rage.

In the past month, temperatures in the Central Pacific have returned to near-normal after three years of cool anomalies, while the waters of the Eastern Pacific have surged warmer, which sometimes presages El Niño development. The official El Niño/La Niña forecast from the National Weather Service has about a 60% chance of El Niño arriving by the peak of hurricane season in September.

Why you should root for El Niño

That’s not the whole story, though. Many sophisticated computer models that simulate the ocean-atmosphere system are going wild, calling for a much faster emergence of strong El Niño conditions by summer. Most “dynamical” models initiate El Niño by August or September. That is all well and good, as the stronger and earlier the Niño, the greater the historical probability of a quieter Atlantic hurricane season.

However, the dynamical guidance has had a pro-Niño bias in other recent springs. In April 2017, several of these models called for a super El Niño by summer; in reality, a weak La Niña developed in the fall, and the Atlantic hurricane season was one of the most active on record.

But it only takes one

Even if El Niño develops, that isn’t a be-all and end-all for U.S. hurricane risks. In 2018, a modest El Niño gradually developed by late September and shut down tropical activity in the Gulf and Caribbean in mid-October… right after a monster Category 5 hurricane slammed the Panhandle.

Here’s what to watch

Expect more clarity in WeatherTiger’s next seasonal forecast update. In the meantime, another key consideration is Atlantic sea surface temperature anomalies. Historically, the strongest relationships between Atlantic spring warmth and an active hurricane season are found between eastern Brazil and West Africa. Warm spring waters there often migrate north into the Atlantic’s Main Development Region by the hurricane season’s peak, promoting more frequent development of tropical waves.

This spring, water temperatures in the eastern Atlantic are well above normal, and more broadly, areas with a positive relationship between spring temps and a more active hurricane season are significantly warmer than normal. This isn’t too surprising as the North Atlantic is the hottest it has ever been for early April, and again, those relationships are still weak this far away from the season. However, unseasonable Atlantic heat more typical of mid-May further ups the stakes of El Niño actually developing, as there’s no indication of Atlantic temps being unfavorable to hurricanes in 2023.