KINGSTON — Sediments in water are finely-grained particles which are traditionally generated as a by-product of natural weathering and soil erosion, but are increasingly the result of human activities, such as container ships, tourists and fishing trawlers.

When they accumulate in large enough quantities, sediments can often threaten the sustainability and survival of marine life by increasing turbulence and reducing visibility in nearby waters. This is because turbid water contains a lot of suspended sediments, reducing the amount of sunlight reaching the ocean floor, in turn reducing photosynthesis and leading to die-offs among marine flora.

Increased turbidity dislodges fish and amphibian eggs, reduces the competitiveness of local species, and reduces the aesthetic quality of water, affecting tourism and recreation. Despite posing a threat to aquatic environments worldwide, each year, between 750,000 and one million tonnes of sediments are discharged into the Caribbean Sea, consequently degrading the marine environment and jeopardizing the regional fishing industries.

Through its technical cooperation program, the International Atomic Energy Agency is supporting Latin American and Caribbean countries to monitor and analyze the scope and scale of sedimentation in the region. The analyses and the data they produce are crucial to the development and implementation of preservation efforts.

Training provided by the IAEA focused on the sampling, monitoring and study of growing sedimentation in the Caribbean and its effects on marine life, using the radioisotope of lead, 210Pb—that training has now culminated in the publication of a November 2020 study published in the Journal of Environmental Radioactivity.

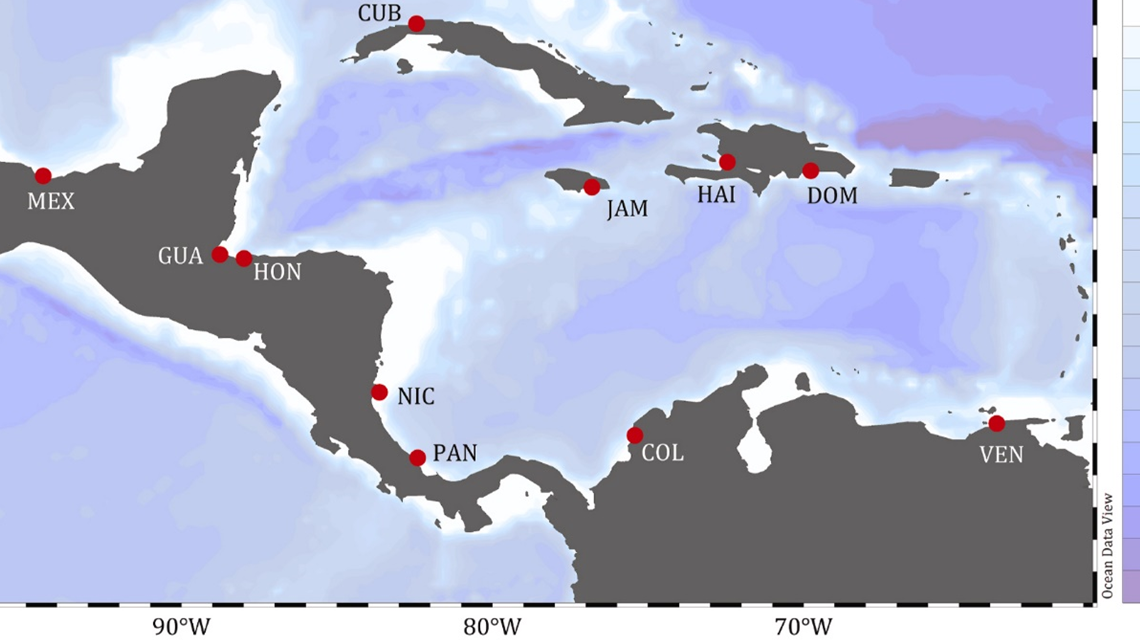

The sediment core collection sites were the bays of Cartagena (Colombia), Havana (Cuba), Amatique (Guatemala), Port-au-Prince (Haiti), Puerto Cortes (Honduras), Bluefields, (Nicaragua) and Admiral (Panama). Additionally, the estuaries of the Haina River (Dominican Republic) and the Coatzacoalcos River (Mexico), the Port of Kingston (Jamaica) and the Gulf of Cariaco (Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela) were also studied. (Photo: Ruiz-Fernandez/ Institute of Marine Sciences and Limnology)

The first such assessment carried out in the Caribbean Sea, the study found that sedimentation and siltation have been rising in the region since the beginning of the 20th century, due primarily to deforestation, soil erosion and poor urban and industrial waste management. In addition to clarifying the scale of the sedimentation challenge in the Caribbean, this study provides baseline data upon which decision-makers can measure the success of new policies and initiatives.

Undertaken within the framework of the Marine Coastal Research Network (REMARCO), established in 2018 under the auspices of an ongoing regional TC project, the study analysed sediment cores from coastal environments in 11 countries – Colombia, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama and Venezuela. It identified an eight to 21-fold increase in the accumulation of sediments, when compared with the beginning of the last century. By dating the collected samples with a radioisotope of lead, 210Pb, scientists were able to simulate, model and eventually determine when and in what quantities sediments had accumulated. Increasing rates were mostly attributed to continental erosion, likely associated with land use changes in the catchment areas of major rivers.

“The reasons for the increase are varied. These include drainage systems which unload into the sea, deforestation and bad agricultural practices,” explained Ana Carolina Ruiz-Fernández, an academic at the Institute of Marine Sciences and Limnology at the National Autonomous University of Mexico and co-author of the study. “Logging and burning forests to clear areas for agriculture and monocultures cause soil retention capacity to be lost and end up as sediments on the coasts,” she added.

The presence of sediments can jeopardize biodiversity and are of particular concern due to the economic value of the marine environment to the Wider Caribbean Region—approximately 60 per cent of the Gross National Products of countries in the region depend upon the health and condition of the Sea.

Coastal zones along the Caribbean Sea are often heavily populated and subject to environmental pollution originating from human activity. In the absence of regional monitoring programmes, the long-term effects of these pressures on the health and sustainability of the marine ecosystem cannot be accurately assessed.

Building capacities of marine laboratories

A series of TC projects that began in 2007 and are ongoing have contributed to building capacities among the participating countries in Latin America and the Caribbean in monitoring the growing sedimentation in the Caribbean. The IAEA organized regional workshops and training courses on the sampling and processing of sediment cores, on the fundamentals of the geochronology of coastal and marine sediments, and on the application of 210Pb dating models to study environmental changes in coastal sediments.

The projects also provided the participating national laboratories with minor equipment and consumables, such as gravity corers, to sample sediment layers, as well as drying and muffle ovens, used to remove water and otherwise prepare the samples for study. In parallel, regional analytical capacities were established and enhanced with capabilities for the analysis of gamma (Colombia and Mexico) and alpha emitters (Cuba and Nicaragua), mercury (Nicaragua) and for X-ray fluorescence analysis (Cuba).

At least 20 professionals from the region received hands-on training at specialized labs and learned how to conduct radiometric measurements, identify contaminants within sediment samples and interpret the laboratory results.