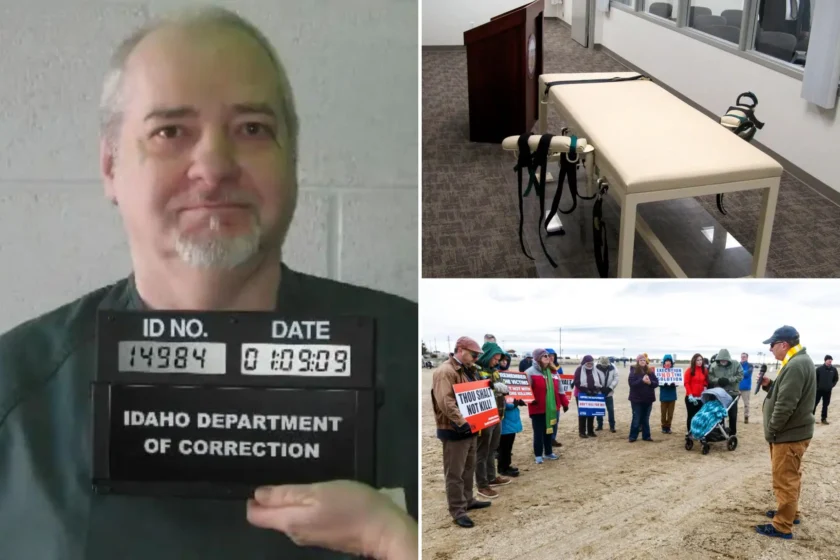

KUNA, Idaho (AP) — For nearly an hour, Thomas Eugene Creech lay strapped to a table in an Idaho execution chamber as medical team members poked and prodded at his arms and legs, hands and feet, trying to find a vein through which they could end his life.

After eight attempts Wednesday, the prison warden told them to give up. Creech, a 73-year-old serial killer who has been in prison for half a century, was returned to his cell — for how much longer, no one knows.

The botched lethal injection was the latest in a string of difficulties states have had carrying out such executions since Texas became the first state to use the method in 1982.

Here’s a look at things to know about Creech’s case and what comes next.

What happened?

Creech, one of the longest-serving death row inmates in the U.S., had a last meal of fried chicken and gravy Tuesday night. He was wheeled into the execution chamber at the Idaho Maximum Security Institution on a gurney at 10 a.m. Wednesday, where he was to die for one of his crimes: the 1981 beating death of a disabled fellow inmate who was serving time for car theft.

Three medical team members tried eight times to establish an IV, Department of Correction Director Josh Tewalt said. In some cases, they couldn’t access the vein, and in others they could but had concerns about vein quality.

At one point, a medical team member left to gather more supplies. The warden announced they were halting their efforts at 10:58 a.m.

It’s not clear why they had trouble. A variety of factors can affect the accessibility of someone’s veins, including dehydration, stress, room temperature or physical characteristics. Creech’s attorneys have said he suffers from several illnesses including Type 2 diabetes, hypertension and edema. Those illnesses could impact circulation and vein accessibility.

Medical experts also say the experience of the professional inserting an IV line can help determine whether the procedure is successful.

The execution team was made up entirely of volunteers who, according to Idaho execution protocols, were required to have at least three years of medical experience, such as having been a paramedic. They were not necessarily doctors, who famously take an oath to “do no harm.”

The identities and qualifications of the medical team members were kept secret. They wore white balaclava-style face coverings and navy scrub caps to conceal themselves.

What’s next for Creech?

Creech’s death warrant, issued by Fourth Judicial District Judge Jason Scott, said his execution had to be carried out by 11:59 p.m. on Wednesday. When the morning effort to execute him failed, his attorneys rushed to file a new request for a stay in federal court, before the state could try again, saying “the badly botched execution attempt” proves the department’s “inability to carry out a humane and constitutional execution.”

Tewalt, the correction director, quickly announced the state would not try again Wednesday, and the death warrant expired. The state will have to obtain another if it wants to carry out the execution.

“We don’t have an idea of time frame or next steps at this point,” Tewalt told a news conference.

Creech’s attorneys were prepared to keep fighting for his life. The U.S. Supreme Court rejected their last-ditch appeals Wednesday morning.

“This is what happens when unknown individuals with unknown training are assigned to carry out an execution,” the Federal Defender Services of Idaho said in a written statement.

Robert Weisberg, a law professor and the co-director of the Stanford Criminal Justice Center, said Creech’s chances of convincing the Supreme Court justices that a second execution attempt would be cruel and unusual punishment are slim. The court ruled in 1947 that Louisiana could try again to execute a prisoner after an electric chair malfunctioned.

Creech’s attorneys could argue that he has medical conditions that would make lethal injection execution impossible, and that further attempts would be torture, Weisberg said.

Does Idaho have other options?

A number of pharmaceutical companies in recent years have restricted sales of their drugs for use in executions, making access a challenge for states trying to carry out the death penalty. Before Idaho’s last execution, in 2012, Tewalt — who was not yet the corrections department director — and a colleague flew to Tacoma, Washington, with more than $15,000 in cash to buy the drugs from a pharmacist.

The trip was was only revealed after University of Idaho professor Aliza Cover successfully sued for the information under the state public records act.

Against that backdrop, Idaho lawmakers passed a law authorizing execution by firing squad when lethal injection is not available. Prison officials have not yet written a standard operating policy for the use of firing squad, nor have they constructed a facility where a firing squad execution could occur. Both would have to happen before the state could attempt to use the new law, which would likely trigger several legal challenges.

Lawmakers also dramatically increased the secrecy about how the state obtains lethal injection drugs, and about the people or companies involved in supplying the drugs. The law requires that the identification of the execution team members be kept secret, and it prohibits the state’s professional licensing boards from taking disciplinary action against a person who participated in an execution.

“It’s really hard to know what went wrong here,” said Robin M. Maher, the executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center. “That, to me, is the very best argument against these secrecy laws.”

Creech’s attorneys have argued that Idaho’s refusal to say where it obtained the drug it planned to use on Wednesday violated his rights.

What’s happened in other states?

Lethal injection is the main method of execution for the federal government and the 27 states that have the death penalty, including some that now have moratoriums on its use. But there have been some prominent examples of botched efforts.

Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey paused executions for several months to conduct an internal review after officials called off the lethal injection of Kenneth Eugene Smith in November 2022 — the third time since 2018 Alabama had been unable to conduct executions due to problems with IV lines.

Smith in January became the first person to be put to death using nitrogen gas. He shook and convulsed for several minutes on the death chamber gurney during the execution. Idaho does not allow execution by nitrogen hypoxia.

In 2014, Oklahoma officials tried to halt a lethal injection when the prisoner, Clayton Lockett, began writhing after being declared unconscious. He died after 43 minutes; a review found his IV line came loose.

By REBECCA BOONE and GENE JOHNSON/Associated Press

Johnson reported from Seattle.