Lower courts condemned the treatment of Damon Landor, a Rastafarian, but found that a federal law protecting religious rights barred him from suing prison officials for money

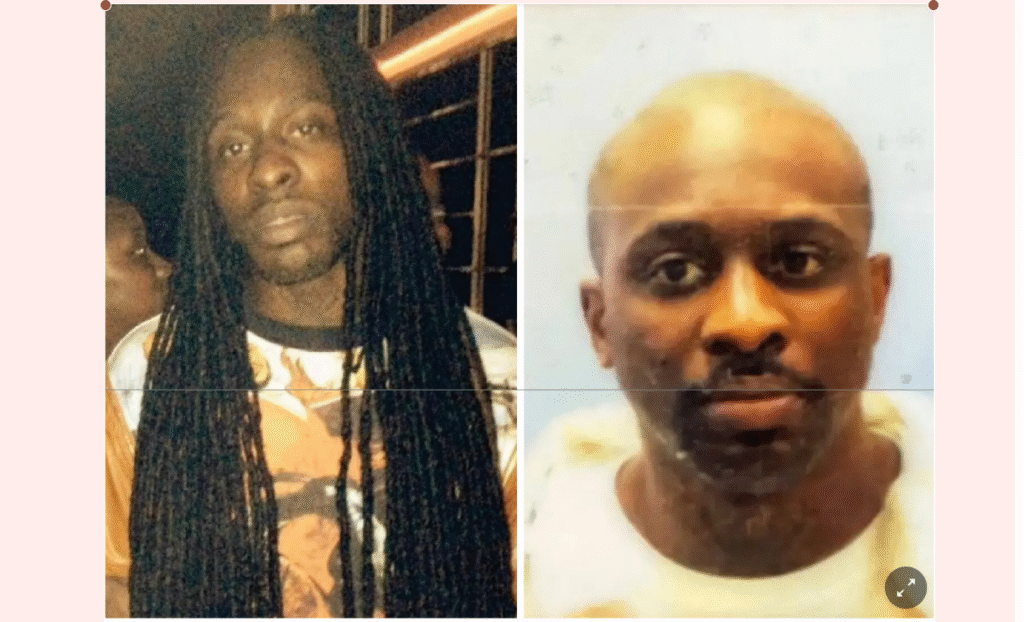

WASHINGTON — Damon Landor, a Rastafarian, was so wary of Louisiana prison officials that he reported to serve a five-month sentence carrying a copy of a legal opinion that found that inmates must be allowed to keep their dreadlocks, under a federal law protecting prisoners’ religious freedom.

Four months into his term for drug possession, Landor, whose faith requires him to let his hair grow long, was transferred to a new prison. When he pulled out a copy of the court’s 2017 decision, a guard threw it in the trash, according to court documents he filed in a later lawsuit.

Then, two guards handcuffed Landor to a chair, restrained him and forcibly shaved his dreadlocks.

The Supreme Court today heard arguments in a case testing whether Landor can sue state prison officials for money for violating his religious rights.

Attorney General Elizabeth B. Murrill of Louisiana, who is defending the prison officials, nevertheless strongly condemned what happened to him in prison. So, too, did lower-court judges who ruled against Mr. Landor. But the appeals court said it was bound by past rulings banning such lawsuits.

The Trump administration and Mr. Landor’s lawyers have urged the Supreme Court to allow the case to proceed.

The Supreme Court has in recent years repeatedly bolstered religious rights. In 2022, the court sided with a Texas death row inmate who wanted his pastor to touch him and pray aloud at the time of his execution. The same year, the court said a high school football coach had a constitutional right to pray at the 50-yard line after his team’s games.

When Landor was transferred to the Raymond Laborde Correctional Center in Cottonport, La., in 2020, he handed a prison guard proof of his religious accommodations — the 2017 court decision, which said that the state’s policy of cutting the hair of incarcerated Rastafarians violated federal protections for religious exercise. At that point, he had not cut his hair for almost two decades and his dreadlocks fell nearly to his knees.

Landor, who is now growing his hair back and plans to be in the courtroom today, has said his dreadlocks are central to his identity and religion.

“When I was strapped down and shaved, it felt like I was raped,” Landor said in a statement last year. “And the guards, they just didn’t care. They will treat you any kind of way. They knew better than to cut my hair, but they did it anyway.”

He sued the warden and the guards under the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act, a federal law that requires states to protect the religious rights of individuals in state institutions.

In a separate case, the Supreme Court ruled in 2020 that a related statute from 1993 — the Religious Freedom Restoration Act — permitted individuals to sue to “obtain money damages against federal officials in their individual capacities.”

Justice Clarence Thomas wrote in that case, Tanzin v. Tanvir, that “in the context of suits against government officials, damages have long been awarded as appropriate relief.”

Landor’s lawyers, led by Zachary D. Tripp, told the Supreme Court that the language in the two statutes was identical and allowed for the same monetary remedies.

Besides, he wrote, the “‘stark and egregious’ facts here viscerally show that damages are essential” to protect religious liberty. Congress did not enact the law, he added, so state officials “could freely ignore it.”

Louisiana’s lawyers told the Supreme Court that Landor could not “copy-and-paste” the rationale from the court’s 2020 decision involving federal officials to find a right to sue state officials for damages.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, the same court that had ruled that the law protected Rastafarian prisoners’ dreadlocks, said it “emphatically” condemned Landor’s treatment. But the judges said they were bound by past precedent that did not allow such litigation against state officials. The statute Landor relied on was meaningfully different, the panel wrote, and did not authorize his lawsuit.

“The same words, placed in different contexts, sometimes mean different things,’” a three-judge panel of the 5th Circuit said, quoting an earlier Supreme Court ruling.

The full 5th Circuit declined to rehear the case, but nine judges asked the Supreme Court to provide direction to the lower courts.

Judge Edith Brown Clement wrote that Mr. Landor “clearly suffered a grave legal wrong.” Prison officials, she wrote, “knowingly violated Damon Landor’s rights in a stark and egregious manner, literally throwing in the trash our opinion holding that Louisiana’s policy of cutting Rastafarians’ hair violated the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act before pinning Landor down and shaving his head.”

But whether he can sue prison officials for money, Judge Clement added, “is a question only the Supreme Court can answer.”

By ANN E. MARIMOW/New York Times

Adam Liptak contributed reporting.

Ann E. Marimow covers the Supreme Court for The New York Times from Washington.