SALT LAKE CITY — A federal judge in Utah has issued a landmark ruling that the Constitution grants birthright citizenship to those born in American Samoa, and the attorney for plaintiffs in that case said Friday he’s looking to file additional lawsuits in the U.S. Virgin Islands that could expand voting rights for future generations.

A U.S. territory since 1900, those born in American Samoa have been considered American nationals without the full rights of citizenship. Residents of all other territories, including the U.S. Virgin Islands, have birthright citizenship that was granted by a Congressional law passed in 1929.

American Samoans have pledged allegiance to the United States and followed its laws. Yet they have not been automatically granted citizenship at birth, which left many unable to vote and ineligible for certain government jobs.

On Thursday, a federal judge ruled that American Samoans should be granted United States citizenship and ordered the government to issue them passports reflecting that status. The judge, Clark Waddoups of United States District Court in Utah, cited the 14th Amendment, which guarantees citizenship to any child born in the United States.

The decision reignited a century-long debate about the citizenship status of people born in the territories of the United States. But it is likely just one shot in a continuing legal battle. On Friday, Judge Waddoups stayed his ruling until the case is resolved on appeal.

Practically speaking, that means American Samoans will not be able to register to vote or be granted passports reflecting their status as citizens until a higher court weighs in, said Neil C. Weare, the president and founder of the Equally American Legal Defense and Education Fund, which filed the lawsuit for American Samoans seeking citizenship.

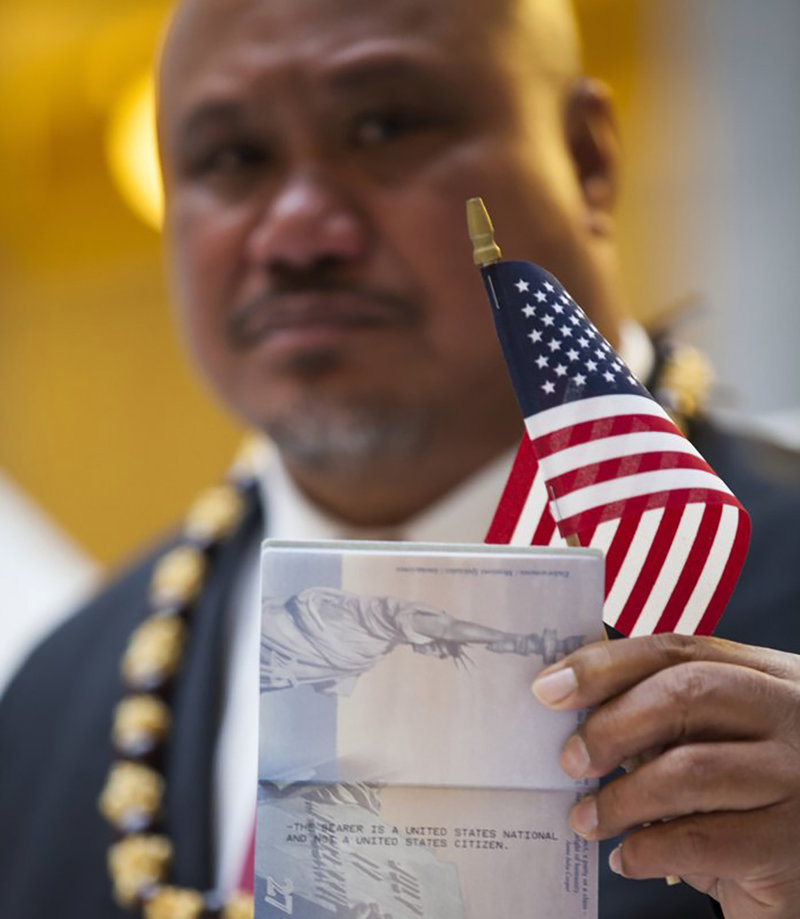

American Samoa, about 2,500 miles southwest of Hawaii in the South Pacific, is the only territory of the United States whose residents are not automatically granted citizenship at birth. The other territories, including Puerto Rico, Guam and the U.S. Virgin Islands, have been granted citizenship by acts of Congress. But American Samoans are classified as “noncitizen nationals” and their passports carry a disclaimer: “The bearer is a United States national and not a United States citizen.”

The government of American Samoa has opposed automatic citizenship for its residents, arguing it would threaten the territory’s traditional cultural and religious practices.

But the plaintiffs in the Utah case, who include three state residents born in American Samoa, argued that classifying them as noncitizen nationals amounted to a “badge of inferiority” that perpetuated an American “caste system.”

Without citizenship, the plaintiffs argued, American Samoans are effectively subject to taxation without representation, and are ineligible to work as police officers, firefighters, military officers, border patrol agents and F.B.I. agents. They also contended that they face a more difficult path than American citizens when sponsoring relatives for immigration.

“It’s been a struggle for so many — they pay their taxes, they do what they’re supposed to do, but they can’t have a job in the police force and do other things because they’re not citizens,” said Susi Lafaele, co-founder of the Southern Utah Pacific Islander Coalition, one of four plaintiffs in the case. “This decision not only gives them the right to vote, but gives that sense of pride of being part of the United States.”

John Fitisemanu, a 54-year-old resident of Woods Cross, Utah, who was the lead plaintiff in the case, said he registered to vote for the first time on Friday morning, just before Judge Waddoups stayed the ruling.

“It’s overwhelming,” said Fitisemanu, who works at a medical testing company and has lived in Utah for more than 20 years. “But I’m most excited to be able to call myself a citizen of the United States of America at this time. It’s been a long time coming.”

Fitisemanu had argued in court papers that it was unjust to deny him the same rights as other Americans and that he was distressed that some assumed he was merely choosing not to vote or was a foreigner.

Representative Aumua Amata Coleman Radewagen, a Republican who represents American Samoa in Congress, said she was disappointed in the decision and argued it would “come as a surprise to tens of thousands of American Samoans that a federal judge in Utah has ruled that they are now United States citizens.”

“While there is room for American Samoans to have different opinions about whether to seek United States citizenship, there are deep concerns about having a distant federal judge decide these issues,” Ms. Radewagen said, adding that the decision would be appealed.

Judge Waddoups ruled that American Samoans must be granted citizenship under the 14th Amendment, which was ratified in 1868 to extend citizenship to African-Americans after the abolition of slavery.

The amendment states, “All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

President Trump provoked backlash last year when he declared that he wanted to abolish birthright citizenship, calling it “frankly ridiculous” and a “magnet for illegal immigration.”

Judge Waddoups wrote that the amendment’s language clearly applies to American Samoans.

“American Samoans owe permanent allegiance to the United States,” Judge Waddoups wrote. “They are therefore ‘subject to the jurisdiction’ of the United States.” And because American Samoa is “within the dominion of the United States,” the territory must be considered part of the country, he wrote.

The government, Judge Waddoups wrote, “shall issue new passports to plaintiffs that do not disclaim their U.S. citizenship.”

Judge Waddoups did not immediately respond to a request for comment on his decision to stay the ruling on Friday.

The Justice Department, which opposed the lawsuit, did not immediately respond to a request for comment on Friday.

In court papers, the department’s lawyers argued that the Constitution does not require birthright citizenship for anyone born in an unincorporated territory and that “any remedy here must come from Congress, not the federal judiciary.”

American Samoans ceded sovereignty to the United States by treaty in 1900, according to the Department of the Interior.

The fact that some are still litigating their citizenship rights more than a century later is a vestige, in part, of historical racism, reflecting 19th-century fears that nonwhite residents of American territories would automatically become citizens, said Sam Erman, a law professor at the University of Southern California and author of “Almost Citizens: Puerto Rico, the U.S. Constitution and Empire.”

Erman filed a brief in the case, arguing that American Samoans should be granted citizenship under the 14th Amendment.

“My guess is the litigation campaign will continue,” Erman said.

Weare noted that Judge Waddoups’s decision conflicts with a 2016 ruling by the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, which found that the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of birthright citizenship did not apply to American Samoans. The Supreme Court declined to hear that case on appeal, but could revisit the issue again, he said.

He discussed the ruling Friday at a meeting of the Virgin Islands Bar Association on St. Croix, and lauded the organization for filing numerous amicus briefs in various cases that seek to expand civil liberties for Virgin Islands residents.

“We’re looking to actually potentially file some new cases on behalf of Virgin Islanders, and specifically we’re looking for current residents of the Virgin Islands who used to live in California, Florida, or Hawaii,” Weare told the Virgin Islands Daily News. “We’d be interested in hearing from anybody that wants to vote for President in this next election who are residents of the Virgin Islands” that formerly had residency in those three states.

Equally American previously brought a similar case in an effort to expand voting rights, “so we’re hoping to do that again, and looking for individuals to represent,” Weare said.

Anyone interested in potentially being a plaintiff in such a case is asked to email Weare at [email protected]