MIAMI (AP) — Friends and colleagues of Manuel Rocha knew him for an aristocratic, almost regal, bearing that was fitting for an Ivy League-educated career U.S. diplomat who held top posts across Latin America.

So former CIA operative Félix Rodríguez was dubious in 2006 when a defected Cuban Army lieutenant colonel showed up at his Miami home and told him Rocha was actually a Cuban spy.

“No one believed him,” Rodríguez said, adding he passed the tip along to a similarly skeptical CIA. “We all thought it was a smear.”

That exchange took on new relevance after Rocha was arrested in December and charged with serving as a secret agent of Cuba since the 1970s. In the weeks since, FBI and State Department investigators have been working to decipher the case’s biggest missing piece: exactly what the longtime diplomat may have given up to Cuba.

Here are some key findings from an Associated Press investigation into Rocha’s alleged betrayal and the missed red flags that could have helped him avoid scrutiny for decades.

WHO IS MANUEL ROCHA?

The Justice Department’s case against Rocha dates back to 1973, the year he graduated from Yale. The FBI says he traveled to Chile that year and became a “great friend” of Cuba’s intelligence agency, the General Directorate of Intelligence, or DGI.

Authorities also are scrutinizing the first of Rocha’s three marriages that began around that time, according to those who have been questioned by the FBI.

Rocha was born in Colombia and at age 10 moved with his widowed mother and two siblings to New York City. A talented soccer player with a sharp intellect, he won a scholarship for minorities in 1965 to attend The Taft School, an elite boarding school in Connecticut, catapulting him overnight into a refined world of American wealth.

But as one of the few minorities at the school, Rocha says he suffered discrimination, something that friends now suspect may have fueled a grudge that led him to admire Fidel Castro’s revolution.

WHAT DID HE DO FOR CUBA?

Prosecutors have ranked Rocha’s betrayal among the most brazen in U.S. foreign service history. But the 15-count indictment offers few details about what he allegedly did for Cuba.

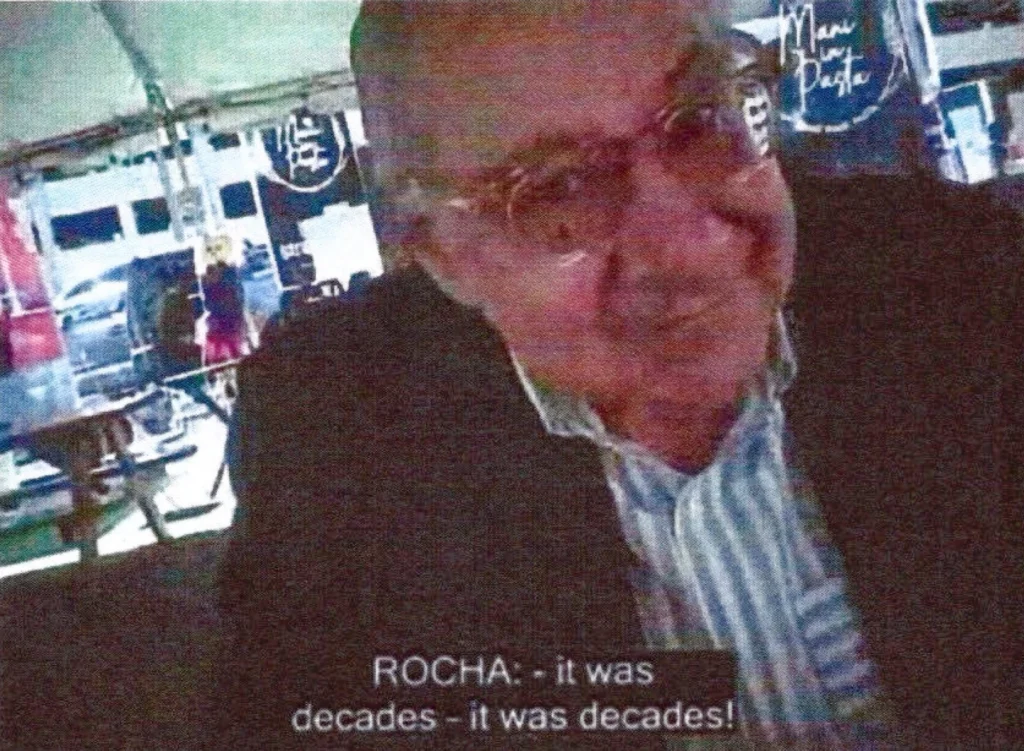

What is known is that an undercover FBI agent secretly recorded Rocha praising Fidel Castro as “El Comandante” and calling his work for Cuba’s communist government “more than a grand slam” against the U.S. “enemy.”

One former colleague, Liliana Ayalde, recalled a 2002 controversy in which Rocha, then serving as ambassador to Bolivia, intervened in that country’s presidential election to help a Castro protégé.

Rocha warned Bolivians that voting for a narcotrafficker — a not-so veiled reference to coca grower-turned- presidential candidate Evo Morales — would lead the U.S. to cut off all foreign assistance.

The comments amounted to Rocha’s biggest known favor for Cuba. Ayalde, who later served as U.S. ambassador to Paraguay and Brazil, now wonders whether it was an act of self-sabotage, done at the direction of a foreign power to further damage the U.S.’ standing in Latin America.

“Now that I look back,” she said, “it was all part of a plan.”

Rocha’s attorney did not respond to messages seeking comment.

WHAT RED FLAGS WERE MISSED?

Authorities are conducting a damage assessment that’s expected to take years, retracing Rocha’s steps and speaking with former colleagues and officials about their interactions with him.

Among those they interviewed is Rodríguez, the former CIA operative who participated in the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion in Cuba and the execution of revolutionary “Che” Guevara.

Rodríguez told the AP that he believed at the time he received the tip from the Cuban defector in 2006 it was an attempt to discredit a fellow anti-communist crusader.

“I want to look him in the eye and ask him why he did it. He had access to everything,” an angry Rodríguez said.

It wasn’t just Rodríguez’s tipster — whom he refused to identify to the AP but says was recently interviewed by the FBI. Officials told the AP that as early 1987, the CIA was aware Castro had a “super mole” burrowed deep inside the U.S. government.

Some now suspect it could have been Rocha and that since at least 2010 he may have been on a short list given to the FBI of possible Cuban spies high-up in foreign policy circles.

The FBI and CIA declined to comment, and the State Department didn’t respond to requests.

“This is a monumental screw-up,” said Peter Romero, a former assistant secretary of state for Latin America who worked with Rocha. “All of us are doing a lot of soul searching and nobody can come up with anything. He did an amazing job covering his tracks.”

By JOSHUA GOODMAN and JIM MUSTIAN/Associated Press

Goodman is a Miami-based investigative reporter who writes about the intersection of crime, corruption, drug trafficking and politics in Latin America. He previously spent two decades reporting from South America.

Mustian is an Associated Press investigative reporter for breaking news.

Contact AP’s global investigative team at Investigative@ap.org or https://www.ap.org/tips/