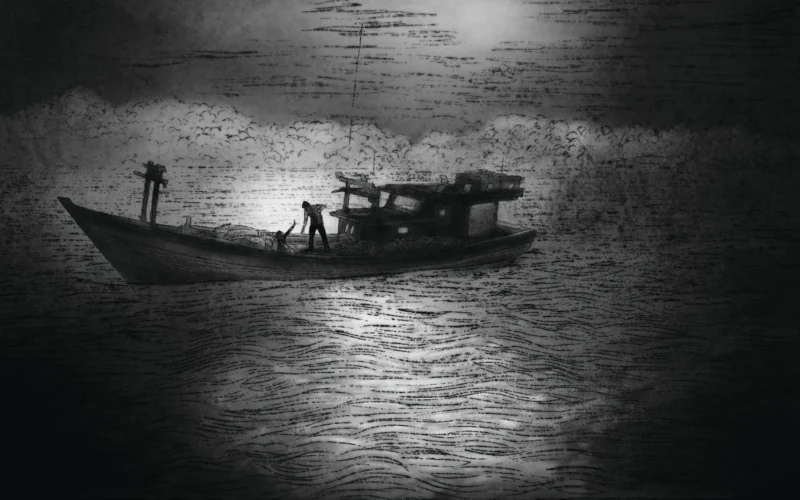

MEULABOH, Indonesia (AP) — The boat glided across waters that were dark and still, under a night sky that was cloudless and calm. But on board, the 12-year-old girl quaked with fear.

The captain and crew who she says had tortured her and three other women and girls were not finished. And the punishment for disobedience, the men warned, would be death.

It was the third night that the girl and around 140 other ethnic Rohingya refugees had been trapped on the wooden fishing boat, floating off the coast of Indonesia. These children, women and men had fled Bangladesh and their homeland of Myanmar in a bid to escape violence and terror, only to face the same horrors with a crew that seemed to delight in their dread.

N, a 12-year-old ethnic Rohingya refugee identified by The Associated Press with only an initial, because she is a sexual assault survivor, stands in her tent at a temporary shelter in Meulaboh, Indonesia, on Thursday, April 4, 2024. (AP Photo/Reza Saifullah)

Huddled among the other women and girls, the 12-year-old — identified in this story only by the initial N, because she is a sexual assault survivor — tried to hide her face. She had already survived a night in the captain’s bedroom, where she says he and several crew members had beaten and sexually abused her.

Like most of the passengers, she had survived attacks by Myanmar’s military that forced her and her family to flee to neighboring Bangladesh. There, she had survived nearly seven years in violence-plagued refugee camps. And she had thus far survived this journey without her family, who hoped she’d make it to Malaysia, where she was promised as a child bride to a man she had never met.

Her young life had been one long battle to survive. And so, it seemed, this night would be no different.

The captain was in a rage. He ordered more girls to join him and his crew in the bedroom.

No one budged.

“If you don’t come to us,” the captain shouted, “then we will capsize this boat!”

What happened next would force N and the other Rohingya on board into yet another battle for survival.

For many, this would be the battle they finally lost.

Ethnic Rohingya refugees stand on their capsized boat as rescuers throw a rope to them off West Aceh, Indonesia, on Thursday, March 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Reza Saifullah)

In March, Indonesian officials and local fishermen rescued 75 people from atop the overturned hull of a boat off the coast of Indonesia’s northern province of Aceh. Another 67 passengers, including at least 28 children, had been killed when the boat capsized, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

Until now, little was known about how the boat capsized, or why. This account, as told to The Associated Press in separate interviews with eight surviving passengers, provides the first insight into what happened on board and why so many died. The men, women and children interviewed include witnesses of the events leading to the capsize and of the sexual abuse, as well as the only surviving sexual assault victim, N.

The disaster is the latest in a string of tragedies to befall the Rohingya, a stateless Muslim minority that suffered mass slaughter at the hands of Myanmar’s military in 2017 in what the United States has dubbed a genocide. Over the past two years, the Rohingya have increasingly fled Bangladesh’s refugee camps, where gang violence and hunger has surged, and Myanmar, where a bloody conflict between the ruling military junta and ethnic rebel groups has escalated. Muslim-majority Malaysia, which the Rohingya view as relatively safe, is the preferred destination.

The results of this mass exodus have been catastrophic. Last year, 4,500 Rohingya — two-thirds of them women and children — fled Myanmar and Bangladesh by boat, the UNHCR reported. Of those, 569 died or went missing while crossing the Bay of Bengal and Andaman Sea, the highest annual death toll since 2014.

Rescuers recover the body of a Rohingya refugee from the waters off Meulaboh, Indonesia, on Saturday, March 23, 2024. (AP Photo/Reza Saifullah)

International indifference toward the Rohingya has, in many ways, worsened the crisis. In several cases, coastal countries in Asia have ignored pleas to rescue imperiled Rohingya boats, despite international laws mandating the rescue of boats in distress. Global donations for the nearly 1 million Rohingya languishing in overcrowded camps have plummeted, leading to slashed food rations. And no country is offering large-scale resettlement.

Most Rohingya understand the risks of taking to the sea. But those who board the vessels say the world has left them with little choice.

And so it was that N arrived one night in March at a remote beach in southern Bangladesh, where she climbed into a small fishing boat that would take her away from everything she knew, including her family.

Like an increasing number of underage Rohingya girls, she had been promised as a wife to a man in Malaysia she’d spoken to only by phone. These marriages are rooted in desperation: Many parents in the camps can no longer feed their children or afford the traditional dowry demanded by grooms. The men in Malaysia forfeit dowries and often send money to the brides’ parents.

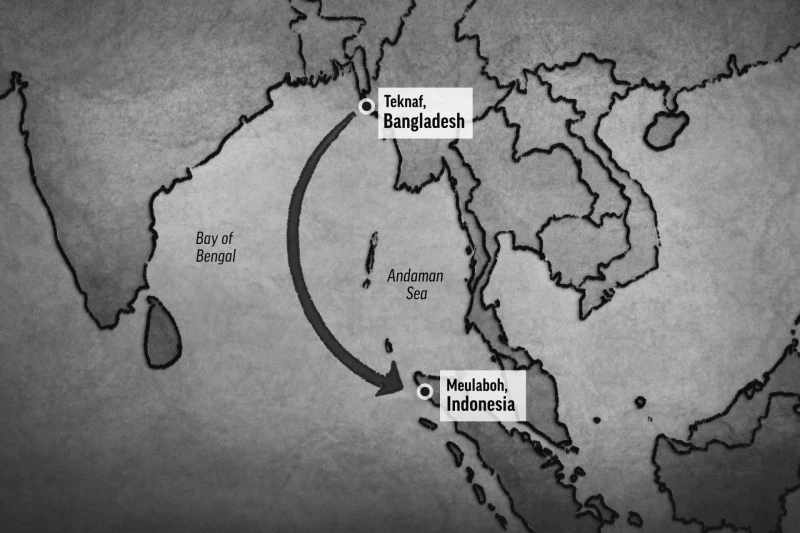

The fishing boat ferried N and her fellow passengers to a larger boat, which took them deeper into the Bay of Bengal. One day later, they were moved again to an even bigger boat, with a crew from Myanmar.

Rohingya refugees rest on the deck of a National Search and Rescue Agency ship, after being rescued from their capsized boat off West Aceh, Indonesia, on Thursday, March 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Reza Saifullah)

For around a week, they slid seamlessly through the sea. The crew was kind, providing enough food and water. The children had space to play. The waves were placid. For Rahena Begum, traveling with her 9-year-old daughter and 12- and 13-year-old sons, it almost felt too easy.

Until suddenly, it wasn’t.

The captain told those on board the plan had changed. They would need to transfer everyone to an Indonesian fishing boat, with a crew who would take them the rest of the way to Indonesia. From there, the passengers would be smuggled into neighboring Malaysia. Though the captain gave no reason for the switch, the recent surge in Rohingya arrivals has put Indonesian authorities on alert for boats from Bangladesh and Myanmar.

The sight of the rickety Indonesian vessel sent a chill through the passengers. Muhammed Amin, who had fished the waters off Bangladesh for years and spent countless hours on boats, estimated the Indonesian vessel was built to accommodate, at most, 60 people — not 140.

An illustrated map showing a general boat route. The Rohingya refugees left from Teknaf, Bangladesh, and their small boat eventually capsized off Indonesia. (AP Illustration)

But the Myanmar captain and crew, he says, reassured him the boat was safe and that it would reach Indonesia in one day.

Reluctantly, Amin, N, Rahena and the others climbed into the Indonesian vessel. The Myanmar boat soon disappeared into the distance.

By EDNA TARIGAN AND KRISTEN GELINEAU/Associated Press