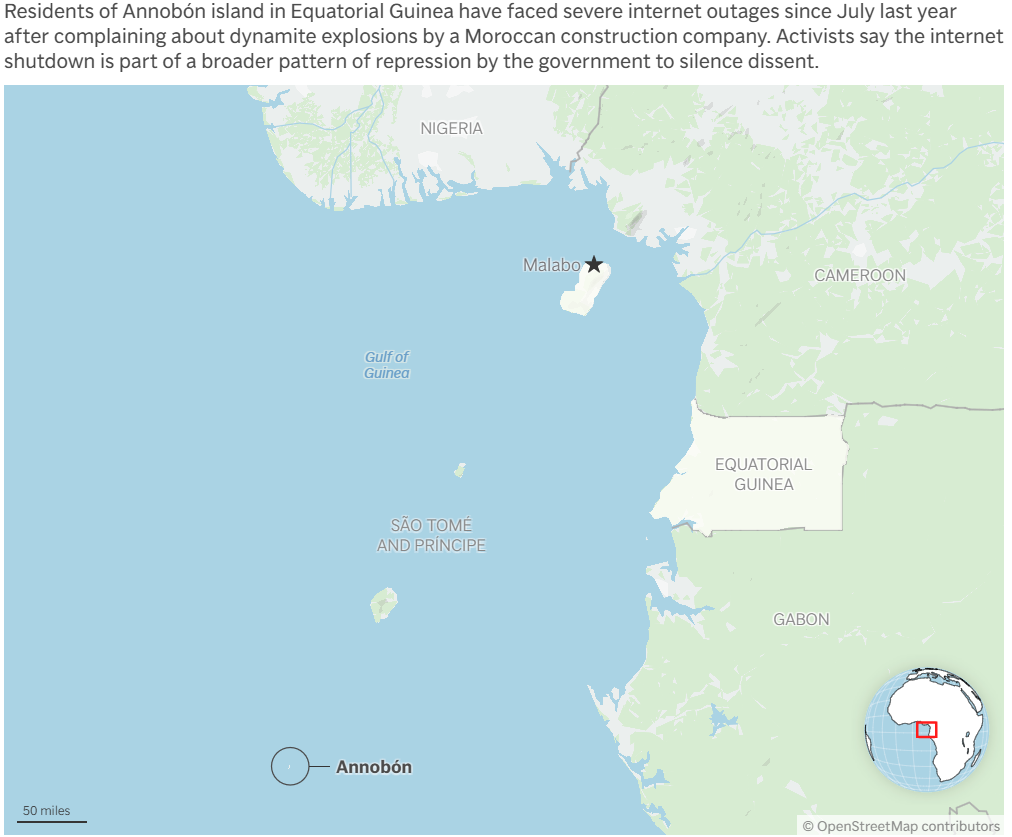

LAGOS, Nigeria (AP) — When residents of Equatorial Guinea’s Annobón island wrote to the government in Malabo in July last year complaining about the dynamite explosions by a Moroccan construction company, they didn’t expect the swift end to their internet access.

Dozens of the signatories and residents were imprisoned for nearly a year, while internet access to the small island has been cut off since then, according to several residents and rights groups.

Local residents interviewed by The Associated Press left the island in the past months, citing fear for their lives and the difficulty of life without internet.

Banking services have shut down, hospital services for emergencies have been brought to a halt and residents say they rack up phone bills they can’t afford because cellphone calls are the only way to communicate.

When governments shut down the internet, they often instruct telecom providers to cut connections to designated locations or access to designated websites, although it’s unclear exactly how the shutdown works in Annobón.

The internet shutdown remains in effect, residents confirmed alongside activists, at a moment when the Trump administration has considered loosening corruption sanctions on the country’s vice president.

The Moroccan company Somagec, which activists allege is linked to the president, confirmed the outage but denied having a hand in it. The AP could not confirm a link.

“The current situation is extremely serious and worrying,” one of the signatories who spent 11 months in prison said, speaking anonymously for fear of being targeted by the government.

Repression ramps up

In addition to the internet shutdown, “phone calls are heavily monitored, and speaking freely can pose a risk,” said Macus Menejolea Taxijad, a resident who recently began living in exile.

It is only the latest of repressive measures that the country has deployed to crush criticisms, including mass surveillance, according to a 2024 Amnesty International report.

Island faces yearlong internet shutdown after protest

Equatorial Guinea, a former Spanish colony, is run by Africa’s longest-serving president, Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, who, at 83, has served as president for more than half his life. His son serves as the vice president and is accused of spending state funds on a lavish lifestyle. He was convicted of money laundering and embezzlement in France and sanctioned by the U.K.

On Friday, the U.N.’s top court declined Equatorial Guinea’s request for France to return a Paris-based mansion confiscated as part of a corruption probe, ruling that the African nation has not shown it has a “plausible right to the return of the building.”

Despite the country’s oil and gas wealth, at least 57% of its nearly 2 million people live in poverty, according to the World Bank. Officials, their families and their inner circle, meanwhile, live a life of luxury.

The Equatorial Guinea government did not respond to the AP’s inquiry about the island, its condition and internet access.

Annobón has a troubled history

Located in the Atlantic Ocean about 315 miles (507 kilometers) from Equatorial Guinea’s coast, Annobón is one of the country’s poorest islands and one often at conflict with the central government. With a population of around 5,000 people, the island has been seeking independence from the country for years as it accuses the government of disregarding its residents.

The internet shutdown is the latest in a long history of Malabo’s repressive responses to the island’s political and economic demands, activists say, citing regular arrests and the absence of adequate social amenities like schools and hospitals.

“Their marginalization is not only from a political perspective, but from a cultural, societal and economic perspective,” said Mercè Monje Cano, secretary-general of the Unrepresented Peoples and Nations Organization global advocacy group.

A new airport that opened in Annobón in 2013, which was built by Somagec, promised to connect the island to the rest of the country. But not much has improved, locals and activists say. The internet shutdown has instead worsened living conditions there, collapsing key infrastructure, including health care and banking services.

Using internet outage to crack down on a protest

In 2007, Equatorial Guinea entered into a business deal with Somagec, a Moroccan construction company that develops ports and electricity transmission systems across West and Central Africa.

Annobón’s geological formation and volcanic past make the island rich in rocks and expands Malabo’s influence in the Gulf of Guinea, which is abundantly rich in oil. Somagec has also built a port and, according to activists, explored mineral extraction in Annobón since it began operations on the island.

Residents and activists said the company’s dynamite explosions in open quarries and construction activities have been polluting their farmlands and water supply. The company’s work on the island continues.

Residents hoped to pressure authorities to improve the situation with their complaint in July last year. Instead, Obiang then deployed a repressive tactic now common in Africa to cut off access to internet to clamp down on protests and criticisms.

This was different from past cases when Malabo restricted the internet during an election.

“This is the first time the government cut off the internet because a community has a complaint,” said Tutu Alicante, an Annobon-born activist who runs the EG Justice human rights organization.

The power of the internet to enable people to challenge their leaders threatens authorities, according to Felicia Anthonio of Access Now, an internet rights advocacy group. “So, the first thing they do during a protest is to go after the internet,” Anthonio said.

Somagec’s CEO, Roger Sahyoun, denied having a hand in the shutdown and said the company itself has been forced to rely on a private satellite. He defended the dynamite blasting as critical for its construction projects, saying all necessary assessments had been done.

“After having undertaken geotechnical and environmental impact studies, the current site where the quarry was opened was confirmed as the best place to meet all the criteria,” Sahyoun said in an email.

The residents, meanwhile, continue to suffer the internet shutdown, unable to use even the private satellite deployed by the company.

“Annobón is very remote and far from the capital and the (rest of) continent,” said Alicante, the activist from the island. “So you’re leaving people there without access to the rest of the continent … and incommunicado.”

By OPE ADETAYO/Associated Press

Adetayo is a West Africa reporter for The Associated Press. He covers news and regional development across West and Central Africa.

AP’s Africa coverage at: https://apnews.com/hub/africa