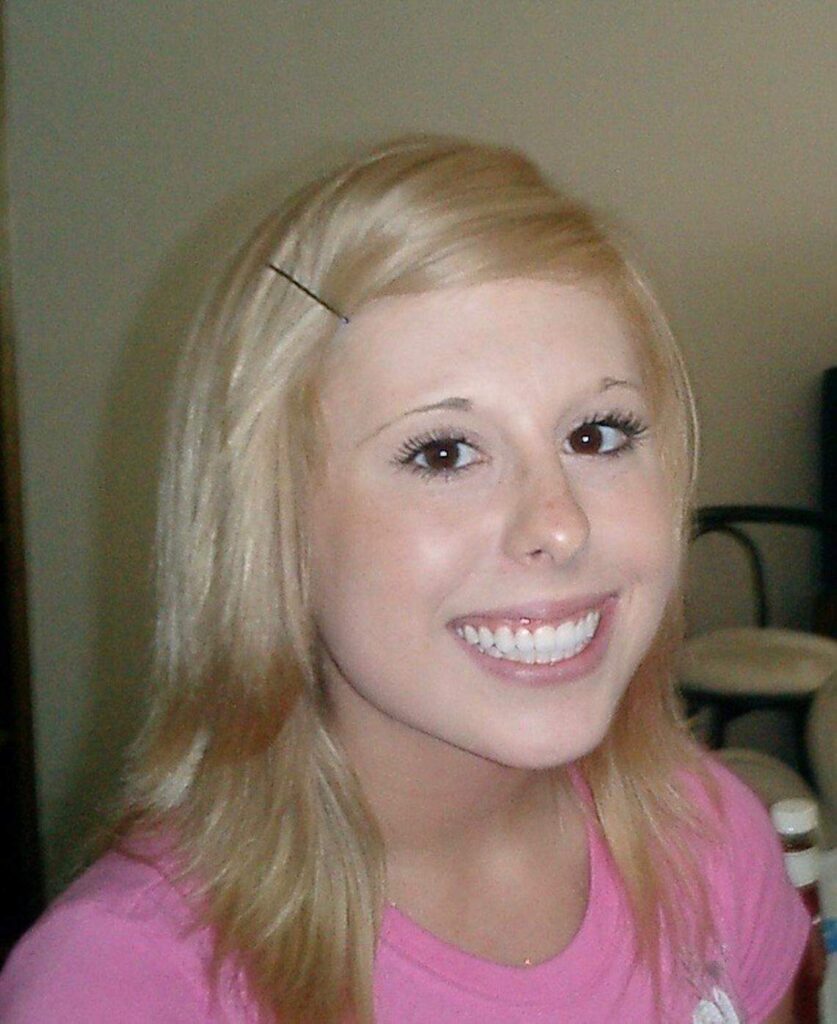

As Mary Catherine Gingles was hunted down by her estranged husband brandishing a semiautomatic handgun equipped with a silencer, authorities say, several Broward Sheriff’s deputies were milling about just outside the Tamarac neighborhood where she and two others would be shot to death – waiting on orders to move.

If the deputies rushed to the scene in the minutes after the first 911 call came in about gunshots in the neighborhood – which they are drilled to do in an active-shooter situation – Mary and the neighbor whose home she sought refuge in may be alive today, according to policing experts — and Broward Sheriff Gregory Tony.

“We had every opportunity to save that woman’s life,” Tony said.

Tony made the remarks at a September 12 news conference announcing that eight BSO deputies had been fired — including a captain previously dismissed in May — for their bungled response to the multiple 911 calls on Feb. 16, the day of the murders. Tony also castigated the deputies for mishandling the 14 calls Mary made to BSO in the year leading up to her death, warning about her estranged husband Nathan Gingles’ increasingly dangerous behavior, which led their 4-year-daughter to tell her mother: “Daddy is trying to make you die.”

A Miami Herald review of almost 300 pages in the BSO investigation of the deputies’ actions detail catastrophic failures in responding to the early Sunday morning murders of the 34-year-old Mary, her 64-year-old father David Ponzer and Andrew Ferrin, the 36-year-old neighbor whose home Mary ran into as she darted from house to house seeking safety. The key findings: The sergeant in charge waffled. Deputies stood by idly. A fellow officer slammed them for not rushing in. A “lackadaisical” attitude permeated BSO’s Tamarac bureau.

The nonchalant response stood in stark contrast to the panicked phone calls from neighbors who reported hearing gunshots on their ordinarily quiet street, the Internal Affairs investigative reports show. One neighbor even remarked on the slow response time while talking to a 911 operator.

“I can’t believe there are this many cops in the neighborhood and no one has responded yet,” the caller said at 6:07 a.m., six minutes into the conversation with the dispatcher about gunshots heard in the neighborhood.

At that point, Mary was running down North Plum Bay Parkway, fleeing her home after she witnessed Nathan, 43, shoot and kill her father as he drank coffee on her back patio around 6 a.m., according to court records charging Nathan with three counts of first-degree murder, along with kidnapping and child abuse. Nathan has pleaded not guilty and faces the death penalty, if convicted.

At least three deputies were already at a “rallying point,” a meet-up spot, on State Street and Nob Hill Road, just outside the Tamarac neighborhood.

“How long have we been on the line, eight minutes?” the same caller said at 6:10 a.m. “They have a really slow response time; they are supposed to be here in seven minutes.”

The failure of the BSO deputies to act urgently in an active-shooter situation echoes the uproar over BSO’s response to the 2018 Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shootings in Parkland. In that mass shooting, BSO deputies waited outside the freshman building as 17 students and faculty members were killed in the Valentine’s Day rampage.

Police officers cannot stand around and wait in active-shooter situations, said Christopher Mercado, a former NYPD lieutenant who is an adjunct professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City. Officers, Mercado said, should be trained to grab their rifle and body armor, if available, and move in quickly — even if by themselves.

“Your job in those situations is to stop the killing, so you will rush to the sound of gunfire,” Mercado said.

Michael Pizzi, a Miami attorney who has both defended police officers in criminal cases and sued police departments for misconduct in his three-decade career, put it more bluntly. BSO’s response to Mary’s calls – and the triple murders – was “one of the worst cases… of police officers either being incompetent or cowardly.”

“When people like Mary cry out for help, [law enforcement] should be helping,” he said. “They had an obligation to put their lives on the line to save her and instead, they failed her.”

Meet-up spot violated training

Broward deputies receive frequent “active killer” training, which instructs them on what to do – and what not to do – when an active shooting occurs, according to the BSO documents. Deputies are expected to immediately respond – and not meet at a “rallying point.”

The first deputy to arrive is expected to spring into action, even if they are the only officer, with the goal that the “rapid response [is] to neutralize the threat.”

After the first 911 call reporting four rounds of gunshots fired — which came in at 6:01 a.m. from the neighbor complaining about the lack of response — BSO Sgt. Travis Allen instructed the Tamarac-area deputies to meet at the “rallying point” outside the neighborhood to team up, the documents show.

At 6:06 a.m., the first deputies arrived there, three minutes after they were dispatched.

At 6:07 a.m, Mary was running through the neighborhood, trying to find an unlocked door as Nathan stalked her.

At 6:08 a.m., another neighbor called 911, saying he heard nine gunshots and screaming.

At 6:09, another neighbor called about gunfire. By 6:10 a.m., five deputies had congregated at the rallying point.

At 6:11 a.m, Allen, the sergeant in charge of the response, declined to call in SWAT teams.

At 6:12 a.m., a neighbor informs dispatcher about the couple’s domestic violence history and that a court-ordered restraining order had been issued against Nathan.

A BSO K-9 deputy assigned to Deerfield Beach, who was the first to arrive on the scene at 6:13 a.m., immediately took note of the response.

In a conversation with another deputy, the K-9 officer said, “Can you get on the radio and ask because they’re f—— standing back.”

In his news conference, Tony called Allen “absolutely a coward” for failing to order deputies to act more decisively.

In statements to BSO Internal Affairs investigators, several of the Tamarac deputies acknowledged they should have rushed to the scene despite Allen’s order to meet at the “rallying point.”

Mercado, the former NYPD lieutenant and John Jay professor, stressed the best practice is for law-enforcement officers to immediately confront active shooters.

“If you don’t respond, you probably won’t keep your job…“ he said. “It’s pretty much understood: You go in and stop the killing.”

Since the triple murders, 21 BSO deputies have been disciplined over their handling of the case. Eight, including Allen, were immediately fired after the Internal Affairs investigation concluded. The International Union of Police Associations, which represents Broward deputies, previously told the Herald it will seek arbitration to prove that “our members could not have done anything different to change the tragic outcome of that day.”

When asked about the “rallying point,” Allen initially told a deputy that he saw nothing wrong with deputies meeting at the location to “formulate a team and go in.” Allen, however, told IA investigators that he should have taken “more of an aggressive approach.”

“I definitely should have again directed my team to flood the area,” Allen said, according to the documents. “And whether it’s lights or sirens…, we direct them to go there. We’re supposed to make contact with the callers. …[W]e’re supposed to make them feel confident that law enforcement is to respond to their location and do something. “

Previous issues in BSO’s Tamarac division

Problems in BSO’s Tamarac district predated the shooting, according to the Internal Affairs report. Training instructors told a BSO lieutenant that senior night-shift deputies in Tamarac were “lackadaisical” in their response and didn’t have the same urgency as other shifts — during staged active-shooter scenarios.

A sad reality about police training, Mercado said, is that there is never enough of it. Training strains already limited staffing, making it difficult for departments to dedicate the time necessary for instruction.

“Policing training means you pull your personnel away from patrol,” Mercado said. Ideally, officers would spend a week each month on tactical drills, medical response, legal updates and scenario-based exercises to prepare for a wide range of situations, he said. In reality, however, that level of training is both “unrealistic and expensive.”

On the morning of the murders, Allen saw Nathan walking with a barefoot Seraphine, he and Mary’s 4-year-old daughter, along North Plum Bay Parkway. He didn’t stop Nathan, and instead called what he witnessed into his radio. Seraphine, who ran to keep up with her father as he chased her mother, cried out to her father, “Daddy, please don’t,” according to BSO records.

“Just find it odd that they are walking around at this time of the morning, and she has no shoes on,” Allen said over the radio, according to the documents.

Several deputies reported hearing Allen make a comment about being scared of Nathan, a U.S. Army veteran who a Broward judge had ordered to surrender his weapons to BSO in the year before Mary’s death. BSO detailed his weapons, silencers and ammunition in a two-page inventory, including the Sig Sauer P320 semiautomatic handgun with silencer that BSO divers fished out of a nearby lake after the murders. Deputies believe it was the gun used in the Feb. 16 shootings.

Allen’s comment, the report says, was along the lines of: “It’s a good thing that the subject wasn’t confronted, because if he were, then maybe [he and other deputies] wouldn’t be there today.”

Allen denied he said that when he spoke to the investigators, saying “…With this guy’s mental state and what he did to those people on scene, I said, possibly if I had to make contact with him, he …possibly would have engaged me. And I said I would have killed him.“

If Nathan had been detained at the time, an Amber Alert would not have been needed to locate Seraphine nearly six hours after the murders in a Walmart in North Lauderdale.

Sergeant had job-performance issues

Allen’s job performance has been a source of concern in the past, according to the BSO documents. He joined BSO in 2006 and had been a sergeant for a year.

In September 2024, Lt. Michael Paparella sent ex-Captain Jemeriah Cooper, the captain who was fired in the aftermath of the murders, a memo about Allen’s performance, including his poor response to shooting calls. Allen was on probation at the time, and Paparella recommended that it be extended.

Paparella said Allen was “flustered” when managing the Aug. 20, 2024, response to a man who threatened to shoot people at a hotel, which was not named in the documents. Allen had established a command post in front of the hotel, and Paparella instructed him to move it because it could be in the line of fire. Allen relocated the command post farther down the street, but superiors later determined that it remained exposed. A few weeks later, Paparella asked Allen if he could spare a deputy for a call that Allen had requested his help, since he was tied up on another case. Allen reassigned one of his deputies and later blamed the shortage of personnel for the failure to maintain a perimeter around a home where a man had threatened to shoot up a pharmacy and a mall.

“I explained that if he didn’t have the resources, he should have told me so I could coordinate additional support,” Paparella wrote, according to the report. “He became upset and tried to argue that it was my fault the perimeter was broken down.”

Paparella said he had daily talks with Allen to address areas of concern, and sometimes Allen would “shut down,” according to the documents. Allen even complained that he was being micromanaged about a week before the Tamarac murders.

Mary’s calls for help

Allen, Deputy Lemar Blackwood, who had trainee Stephen Tapia, now dismissed, with him, and Deputy Eric Klisiak were fired for their response to the shooting. Detective Brittney King, Deputy Daniel Muñoz and Sgt. Devoune Williams were terminated for their handling of the calls Mary made about Nathan’s increasingly unhinged behavior in the months leading up to the murders. (More than 10 other deputies were temporarily suspended for their response to the shooting and Mary’s detailed calls for help.)

Dan Rakofsky, president of the Broward Deputy Sheriff’s Association, previously told the Herald that there was a “rush to prejudge the fired and suspended deputies.

“Within days of this evil crime taking place, the Sheriff made it clear how this investigation would end,” Rakofsky said. “…It is safe to say that this investigation had a predetermined outcome, and that due process was not afforded to our members.” Mary called BSO 14 times in the last year of her life, meticulously documenting her estranged husband’s behavior and repeatedly pleading with law enforcement to help her because she feared for her life.

“[Nathan] has already taken steps to prepare to murder me, but is waiting for the opportune time,” Mary said in a court filing before her slaying.

Despite the voluminous calls to 5987 N. Plum Bay Parkway, Captain Cooper, who led the Tamarac district from 2021 until his firing in May, didn’t know who Mary was until after she was murdered. Cooper told IA his leadership style was hands-off, and he had a dislike for micromanaging, according to the documents.

Cooper lauded his squad, praising the sergeants as “fantastic” and putting the criminal investigations unit “on a pedestal,” according to the report. But one detective stood out to him for the wrong reasons.

“If I had to rate all of my detectives, [Detective King] would fall to the very bottom,” Cooper said.

Failure to investigate car tracker

King was assigned to investigate a tracker that Mary had found on her car in October 2024. The detective didn’t collect the tracker as evidence until two months later, despite it being a felony to place a tracker on a car in Florida.

Allen, who oversaw the community aide who initially responded to Mary’s call, told IA investigators that he was “unaware at the time that placing a tracker on a vehicle was a crime.”

King delegated the case report to Deputy Raul Ortiz, according to the BSO documents. Ortiz said he wrote the report and submitted it to his supervisor, Sgt. Williams. Williams rejected the report, saying the tracker needed to be forensically investigated.

“In my mind, [King] was going to continue investigating the case because I didn’t know how to [handle] the tracker,” Ortiz told the BSO investigators.

Ortiz told King that Mary contacted him, and King replied that she would “take care of it,” the documents say. Ortiz never called Mary again. King, too, didn’t contact Mary – until Jan. 2, 58 days after she was assigned Mary’s case.

Mercado, who has handled domestic violence calls, said that police should contact the victim as quickly as possible because time is of the essence in these incidents.

“With domestic violence, you really have to be proactive with going out there [and] making contact with the family,” he said.

King said her delay was due to Cooper assigning her to another case, she told the BSO investigators. She stopped following up on the tracker investigation on January 23 – three weeks before the murders.

After the murders, King approached Sgt. Williams visibly distraught and admitted, “Sarge, this was my tracker victim.” King said she “wonder[ed] if I could have done more to save her,” according to the documents.

In one of Mary’s last calls to BSO on Dec. 29, she reported a “crazy person kill kit” in her garage that contained duct tape, zip ties and a note with the word ‘waterboarding’ written on it. Deputy Muñoz responded to the home, where he found a distraught Mary.

Mary informed Muñoz about her contentious divorce and told him that home security footage showed Nathan breaking into the home and leaving the backpack.

The deputy told Mary she could dispose of the backpack if she did not want it inside her home. Muñoz, in hindsight, admitted to IA investigators that he could have notified a supervisor but said he didn’t believe there was “imminent danger at the moment.”

Despite law enforcement’s inaction, Pizzi told the Herald he doesn’t believe any of the deputies will be prosecuted, especially considering how a jury acquitted Scot Peterson, the BSO school security officer who failed to confront the Parkland school shooter.

“Unfortunately, there’s no criminal statute that makes it a crime to be lazy, incompetent or not caring,” Pizzi said. “Fire them and sue them, but it’s a stretch to turn it into a crime.”

However, Pizzi said Mary’s family has a “strong case” worth millions in damages against BSO. The handling of the shooting, he said, is inexcusable for the same agency that vowed in the wake of Parkland to never again have an inadequate police response.

“There should be some accountability, not just from the officers, but all the way to the top,” Pizzi said. “Why didn’t they have the right people in the right place? Why were they not properly trained?”

By GRETHEL AGUILA and MILENA MALAVER/Miami Herald