It was 143 years ago on October 1, 1878, when Crucian agricultural laborers set fire to Frederiksted town and western plantations on St. Croix. The objective was to burn all the way east to “Bassin jailhouse,” known today as Fort Christiansvaern.

In those days, Christiansted was called Bassin by Crucians. In 1733, the Danes founded Christiansted town on the site of a former French village known as Bassin.

The agricultural laborers were stopped at Estate Anna’s Hope by Danish soldiers, but not before at least 51 plantations were damaged or destroyed. In the end, one plantation owner, two Danish soldiers and 84 laborers were also killed.

The estimated losses due to property destruction totaled to $600,000, according to Danish historical records. Estates that were destroyed included Good Hope, Wheel of Fortune, Mount Victory, Diamond, Punch, Annaly, Nicolas, Mount Stewart, Two Friends, Canaan, River, Grove Place, Big Fountain, Mon Bijou, Morning Star, La Vallee, Rust-op-Twist, Concordia, Glynn, Jealousy, Hermitage, Upper Love, Lebanon Hill, Dolby Hill and Montpellier. The other estates were Lower Love, Golden Grove, Adventure, Castle Coakley, Work and Rest, Barron Spot, Strawberry Hill, Diamond and Ruby, Clifton Hill, Slob, Bethlehem, Blessing, Anguilla, Fredensborg, Kings Hill, Castle Burke, Paradise, Mannings Bay, St. George’s, Betty’s Hope, William’s Delight, Carlton, Whim, Enfield Green and Concordia (West).

After the July 3, 1848, emancipation of enslaved Africans, the Danish government enacted rules to keep people enslaved by contracts. Hence, the freedom of the agricultural laborers was short-lived as plantation owners began to quickly devise new regulations.

The Labor Law of 1849, which was created by planters and government officials and not by former slaves, bound them and their families to the plantation they worked for. As a result, by signing these contracts the agricultural laborers became enslaved again.

There is an old Crucian saying, “Once a man, twice a child,” and in this case it translated to a man must work his way through the labor class system from the third class, as a child, to first class, then as an adult, and end up as an old man in the third class again. This system of labor described the hardship agricultural laborers faced on St. Croix. Living conditions, health care, wages all were dictated and controlled by plantation owners and the Danish government.

Each October 1, or on what is known in V.I. history as Contract Day, agricultural workers were allowed to leave their plantation and enter contracts with another plantation owner.

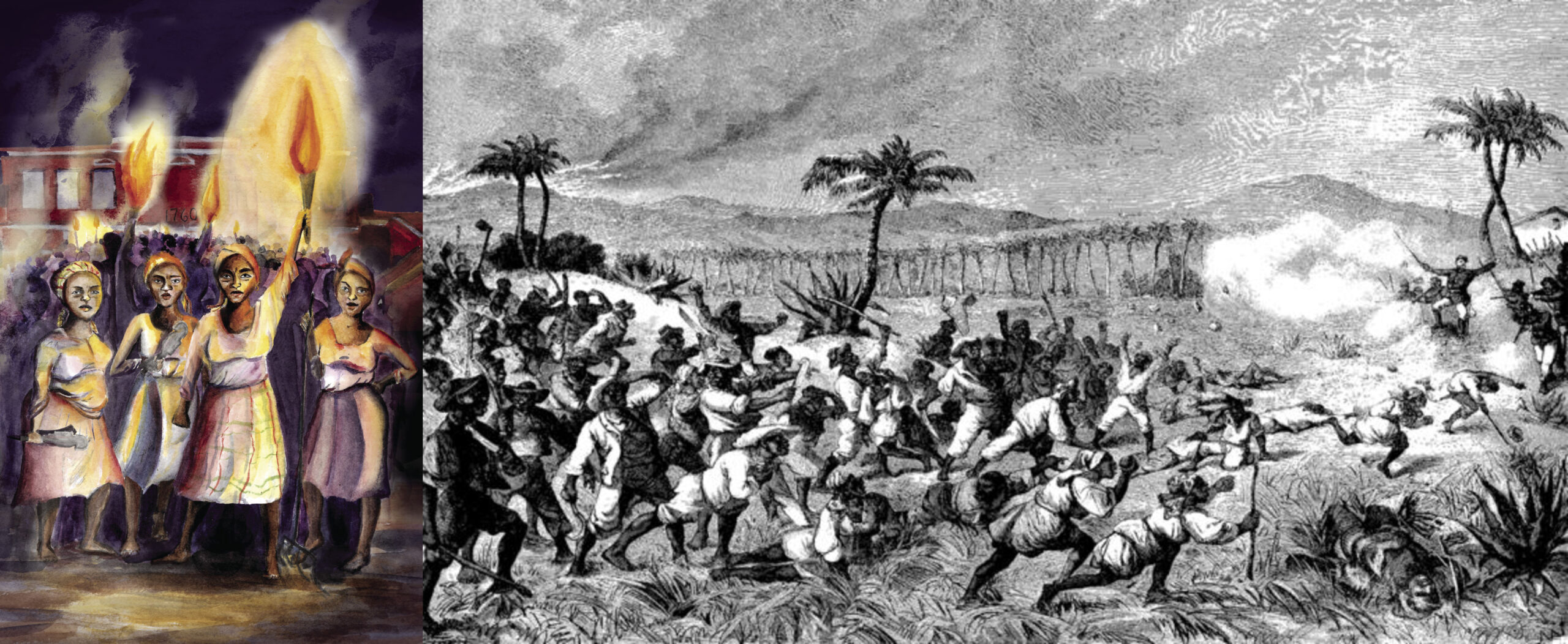

On October 1, 1878, agricultural laborers protested their fixed wages and harsh living conditions. The protest started out peacefully, but eventually the atmosphere changed where fire became the weapon of a just cause for the enslaved population of the Danish West Indies.

The insurrection of the 1878 “Fireburn” was said to be organized and led by four heroines — or queens. Mary Leticial Thomas, better known as Queen Mary (1848-1905), arrived on St. Croix from Antigua in 1860 to work on a plantation. She lived at Estate Sprat Hall. The others were Susannah Abrahamsen/Abrahamson, known as “Bottom Belly,” who lived at Estate Prosperity; Axeline Elizabeth Solomon (Queen Agnes), who lived at Estate Bethlehem; and Mathilde Williams McBean (Queen Mathilda), who lived at Estate Cane.

According to Danish historical documents, more than 400 laborers were arrested, and some were executed by a firing squad. About 40 people were tried and sentenced to prison along with the four queens. The four queens were sent to prison in Copenhagen, Denmark. On July 20, 1882, a Danish newspaper, NYT Aftenblad, stated, “Four negresses, who are sentenced to hard labor for life for their participation in the rebellion on St. Croix arrived yesterday on the ship ‘Thea’ to the capital to serve their sentences to the Women’s Prison on Kristianshavn.”

The Danish newspaper also mentioned a list of 40 prisoners held at Fort Frederik for their involvement in the 1878 Fireburn and what estate they came from. The list included Rebecca Frederick, Estate Cane; John Samuel, Estate Anguilla; Joseph James, Estate Enfield Green; Joseph Briggs, Estate Friedensborg; William Barnes, Estate Rust-op- Twist; Francis Harrison, Estate Prosperity; Emanuel Jacobs, Estate Prosperity; George Simmonds, Estate Barren Spot; James Cox, Estate Diamond; Joseph William, Estate Windsor; Richard Gibbs (Sealey), Estate Barren Spot; and Johannes Samuel, also called “Banborg,” of Frederiksted.

Malvina was the ship that transported Queen Mary as well as Queen Agnes and Queen Mathilde back to St. Croix. The queens departed Denmark on December 18, 1887, and arrived on St. Croix on February 2, 1888, the same year my grandmother Catherine Smalls was born on St. John. Queen Susannah Abrahamsen, known as “Bottom Belly,” came back to St. Croix separately. In May 1886, “Bottom Belly” departed Denmark and arrived on St. Croix on July 21, 1886.

The queens and other agricultural laborers made the ultimate sacrifice for working-class people of the Danish West Indies. As a result, on October 24, 1879, the Labor Law of 1849 was repealed, allowing laborers to freely seek and secure their own employment and to leave the island to seek employment elsewhere.

Queen Mary died March 16, 1905, at age 57 and was buried in Estate William’s Delight Cemetery; Queen Susannah “Bottom Belly” died July 20, 1906, at age 75 and was buried near the Christiansted Cemetery; and Queen Mathilda died Oct. 10, 1935 at age 78 at Estate Hogensborg and was buried in the Catholic Church section of Frederiksted Cemetery.

As Virgin Islanders and Caribbean people, let us not forget the 1878 “Fireburn.”

— Olasee Davis, St. Croix, is an ecologist at the University of the Virgin Islands. He is active in the Virgin Islands’ historical, cultural and environmental preservation