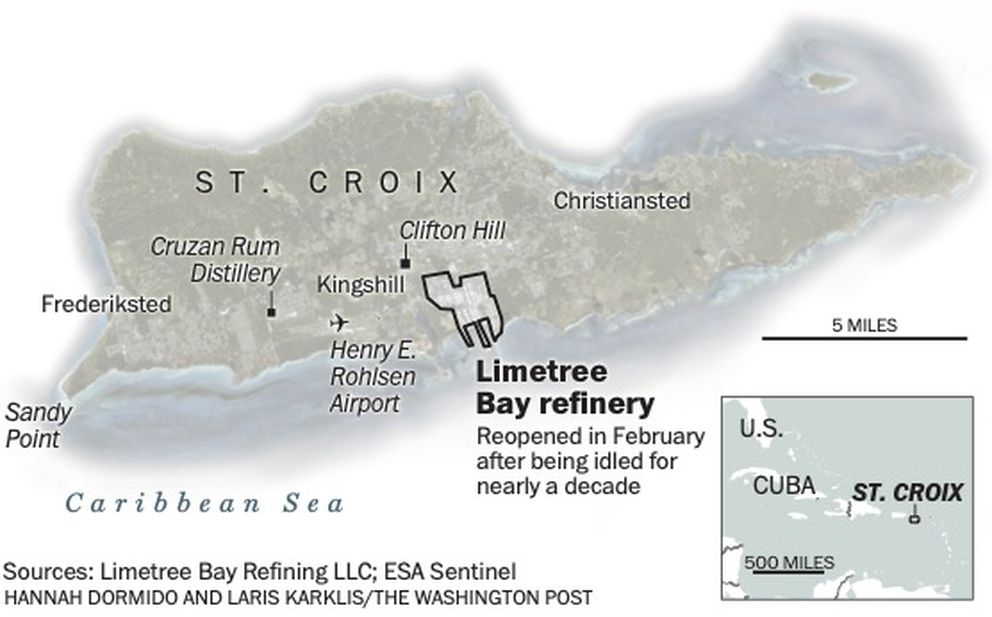

KINGSHILL — Two hours after midnight in St. Croix last month, a filmy vapor rose from a gargantuan oil refinery and floated over nearby homes as quietly as a jumbie in the night

The fine mist of oil and water from Limetree Bay refining rained down on the community of Clifton Hill, showering the slick mix onto cars, gardens, rooftops and cisterns filled with rainwater that residents use for daily tasks.

The vapor, caused by a pressure release valve triggered by an accident on February 4, came three days after the Limetree Bay refinery reopened for the first time in nearly a decade, and the incident prompted the Biden administration to investigate. The Trump administration had approved the reopening of the plant, which had shut down after facing a deluge of lawsuits alleging serious environmental violations.

Three miles from the refinery, Armando Muñoz still sees signs of oil everywhere.

“When it rains it doesn’t wash out, “said Muñoz, 59, who lives with his wife and 78-year-old mother-in-law. “It’s in all the plants we have, avocado trees, and breadfruit trees, and fruit trees and regular household plants.”

The refinery presents one of the earliest tests of President Joe Biden’s vow to clean up pollution in United States’ disadvantaged communities. Ushered back into existence in the waning days of Donald Trump’s presidency, Limetree Bay refinery embodies the difficult tradeoffs Biden faces as he tries to deliver on promises to provide a clean, safe environment and well-paying jobs.

On Thursday, Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Michael Regan withdrew a key permit for the refinery. The move will not close the plant but could lead to tighter pollution controls, marking the administration’s most significant step yet in a campaign to ensure environmental justice.

Asked about the permit decision Tuesday, the EPA declined to comment.

Many officials in the Virgin Islands support the plant, so any federal action poses significant implications. The pandemic has battered the local tourism industry, leaving the refinery and its adjoining logistics hub as a significant source of revenue worth at least $8 million a year to the U.S. Virgin Islands government. The two facilities also employ more than 400 full-time workers, virtually all of them territory residents.

“I’m going to be honest with you, the economy in the Virgin Islands, we were dead,” said Herminio Torres, a community organizer in the Clifton Hill neighborhood.” Retooling the plant brought contractors to the island at a crucial time. “Those workers buy our local food, our local products. The economy has moved forward.”

Company officials said that they are addressing the contamination and that the plant is safe. According to a company report, when water gushed into a drum holding hot coke — an oil byproduct — the reaction triggered a safety valve that relieved the pressure. Refinery flares usually release a mix of water vapor and carbon dioxide: In this case tiny oil droplets entered the air, drifting as far as three miles away.

“Limetree has worked closely with our community and our regulators, investing hundreds of millions of dollars to safely reopen a modernized refinery and create hundreds of high-skilled, well-paying jobs for St. Croix residents,” said company spokesman Erica Parsons.

But the incident has revived uncomfortable memories of the days before the refinery – then called Hovensa – shuttered. Residents recall times when the local high school closed because of the plant’s intense fumes.

On the island’s southern shore between the refinery and Sandy Point National Wildlife Refuge, dozens of oily clumps are once again washing up on the beach, reeking of gasoline.

“You can see the impact for miles,” said Olasee Davis, an ecologist and historian who teaches at the University of the Virgin Islands. “When it comes to the refinery, the refinery always gets its way. The politicians here, they don’t have the political will. People cannot do without it.”

St. Croix — where Biden celebrated New Year’s 2019 with his family, and former vice president Mike Pence sought respite days after leaving office — has idyllic stretches of beaches that offer habitat for leatherback sea turtles, roseate terns and other vulnerable wildlife. But it has also been a quasi-petro state for more than half a century.

The territory’s governor in the early 1960s, a White businessman named Ralph Paiewonsky, struck a deal with Hess Oil Virgin Islands Corp. to construct a refinery on 1,500 acres of the southern shore. On the eve of the deal in 1965, President Lyndon Johnson dismissed concerns raised by a resident that the trade winds would carry the plant’s fumes and waste to the southern shore’s “magnificent beaches.”

“As America grows,” Johnson replied, “private industry will work with local officials and interested citizens to assure the preservation of choice spots of natural beauty and avert some of the unfortunate forms of destruction you describe.”

Named for a partnership between Amerada Hess Corp. and Petróleos de Venezuela,the Hovensa refinery — along with a neighboring aluminum plant and rum distillery — transformed its part of the island into an industrial landscape. The refinery ran a mix of oil and water through pipelines that were buried in the sand and became corroded. By 1982, the company identified underground contamination that ultimately released at least 300,000 barrels of petrochemicals and polluted the island’s one aquifer. In 1994, the EPA determined that all the pipes needed to be replaced.

Lawsuits from local residents, the U.S. Virgin Islands government and the EPA helped speed its demise. Hovensa’s 2011 settlement with the EPA required it to pay a $5.3 million fine and spend $700 million to install modern pollution controls and offset its impact on local residents, including paying more than $300,000 to start a cancer registry. The EPA later determined that at the time of the agreement the plant posed the ninth-highest cancer risk among all U.S. refineries, but the total number of cases is hard to track because the island’s health system is so threadbare that many people seek treatment in Florida or Puerto Rico instead.

After suffering $1.3 billion in losses over the course of three years, the company halted operations in 2012 and declared bankruptcy three years later. The move meant that the company did not pay for a full cleanup, and paid smaller amounts to settle four class-action suits: $4.7 million. Overnight, the territory lost its largest private employer, which accounted for at least 13% of its GDP.

“There was no question that when Hovensa closed the operations in St. Croix, there were close to 4,000 folks that pretty much lost their jobs,” said Kenneth Mapp, who served as the U.S. Virgin Islands governor from 2015 to 2019.

In 2015, a subsidiary of the Boston-based equity firm ArcLight Capital bought the refinery. Its push to reopen had support among Trump administration officials, looking to expand U.S. oil production, and local politicians who were eager to find a new source of revenue. The devastation wrought by Hurricanes Maria and Irma added urgency to the territory’s campaign for fast-track approval.

Mapp, in a letter, appealed to Trump to expedite the reopening “for the benefit of the Nation’s energy independence and the economic resurgence of the Virgin Islands of the United States.”

In August 2018, the EPA head Andrew Wheeler directed EPA appointees to help Limetree Bay “resume operations,” according to documents obtained under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA).

Officials from ArcLight – founded by GOP donor Daniel Revers – and its subsidiary worked with the Justice Department and the EPA to renegotiate the 2011 consent decree to restart the refinery. At one point, according to a document released under FOIA, Limetree Bay and its lawyers expressed “appreciation for [the EPA’s] attention, coordination and responsiveness.”

For Trump appointees at the EPA, the application provided a test case for reinterpreting the Clean Air Act, which the Trump administration sought to weaken. Bill Wehrum, who headed the EPA’s air office from November 2017 until June 2019, wanted to make it easier for industrial operations to expand without being forced to install stricter pollution controls.

In Limetree Bay’s case, that meant the refinery would be treated as if it had never stopped operating, and would not require a new permit.

In meetings with White House officials, Wehrum cited Limetree as a model for how the Trump administration could approve plants across the nation more quickly, said two former federal officials who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss private deliberations.

Relying on a determination that Wehrum provided in an April 5, 2018, letter, Limetree Bay got a permit to operate from the U.S. Virgin Islands government on December 30, 2019.

Limetree Bay also applied to the EPA for a new plantwide permit to process more oil. Trump officials set air emission limits based on the refinery’s production a decade ago, when it processed more than 500,000 barrels a day – even though it planned to produce 200,000 barrels of low-sulfur marine fuel for its main customer, BP.

“We were literally in the dark for months, and not necessarily able to process or understand what was happening with the reopening of the refinery,” said Jennifer Valiulis, who directs the St. Croix Environmental Association.

Parsons said the company spent $100 million on environmental improvements on the plant, and has permanently shut down part of it. “Because Limetree upgraded the facility and reduced its capacity, the Limetree refinery emissions will be much lower than its predecessor.”

Even as the Trump administration helped usher through the company’s applications, it documented how the refinery would affect nearby disadvantaged communities. The EPA found the adjoining neighborhoods — where nearly 27 percent of residents live below the poverty line and 75 percent are people of color — had “high risk vulnerability” to pollution. An earlier 2014 study, by the University of the Virgin Islands Eastern Caribbean Center, found that White residents constituted two percent of area residents.

“There is in fact a disproportionate burden in South-Central St. Croix,” the EPA concluded in 2019, adding that “it is difficult to conclude” that the refinery “will not contribute to a disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effect” on nearby residents.

Shortly afterward, three air policy experts published a Harvard University law school paper criticizing how the Trump administration had interpreted these provisions of the law, singling out Limetree Bay as an example. The paper’s authors included Joseph Goffman, the EPA’s acting assistant administrator for air, who is now with the Biden administration and has been reviewing Limetree’s permit.

The University of the Virgin Islands 2014 study found that nearly twice as many residents “experienced asthmatic conditions during the past five years” compared with those living outside it, and that more than twice as many had chronic bronchitis.

On December 1, 2020 — less than two months before Trump left office — Wheeler took the unusual step of signing the permit allowing Limetree Bay refinery to expand or alter its operations, rather than leaving that to the regional office overseeing the island.

The refinery began producing fuel two months later.

The day it restarted, a coalition of groups — including the St. Croix Environmental Association, the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), the Center for Biological Diversity and the Sierra Club — challenged one of Limetree’s key air permits with the EPA.

Several of these groups are challenging the plantwide permit with the EPA’s Environmental Appeals Board.

John Walke, the NRDC’s clean air director, said the Trump administration’s interpretation of the Clean Air Act violated the law.

Valiulis, of the St. Croix Environmental Association, said that residents remain in the dark and that some have moved out of the area because their health was compromised.

“A lot of people live with cistern water, rainfall off the roof. Whatever goes in there you drink,” she said. “We’re certainly outraged about the process, the lack of information. We don’t know what the monitoring levels are, what they’re allowed to do and if anybody is monitoring.”

Neither the governor’s office nor the territory’s department of planning and natural resources responded to requests for comment.

Mapp said Limetree Bay has provided an economic lifeline for the territory during the pandemic. “Absent of that plant, the government of the Virgin Islands would have been in significant financial problems once its tourism industry was closed.”

Several residents credited the company for being more responsive than its predecessor. According to the company, by March 3 it had contacted or inspected 213 homes, washed 208 cars, cleaned 134 roofs and sampled 135 cisterns. It has been delivering bottled water to many Clinton Hill residents, and it has hired a local claims adjuster to negotiate how to pay for damage.

But residents in the contaminated neighborhood cannot bathe or easily wash dishes with bottled water. Limetree’s contractors confirmed that Muñoz’s cistern is contaminated.

“We are very uncomfortable to hear oil is in the water,” said Muñoz. But he was not surprised. “It had a little odor now and then, sometimes a little taste.”

Sonya Rivera, whose husband, Errol, only ate from their organic garden, said 90% of it was lost because of the incident. “They destroyed all our foods,” she said. “Everything was dead.”

It’s a concern, Rivera said, that Limetree should have addressed more rapidly and never allowed to happen again. “I’m infuriated,” said Rivera, 53. “I know things happen. That plant just opened and things happen. But just take a little more consideration on this community. You know you caused this problem, just rectify it.”

Another resident, Steve, who asked to be identified only by his first name because he is afraid of speaking out against the company, said he heard sirens blare from the refinery on the morning of Feb. 4. But Steve and his family did not understand what the siren meant and didn’t find out about the accident until many days later.

“We didn’t pay it no attention,” he said. “At that time, we were eating and drinking whatever’s there in the water.”

SOURCE: Anchorage Daily News